Levinthal’s paradox is the second question of the protein folding problem, which became too long to be an endnote in my post about DeepMind protein structure prediction so this is sort of an appendix. Epistemic status: Not too sure, somehow almost every paper I’ve read on this is written by Russians.

The Paradox

Levinthal’s paradox states that the number of possible conformations available to a given protein is astronomically large (10300), such that even for a small protein of 100 residues with 3 possible amino acid bond states sampling 1013 new configurations per second, it will take 1027 years to try all 5 x 107 configurations to find the correct one, which is more time than the universe has existed.

However, for in vivo folding, the average time for protein synthesis is about 0.1 s per amino acid residue in both bacterial and eukaryotic cells, while the spontaneous folding time of single-domain globular proteins ranges from a fraction of a microsecond per residue for small proteins to many seconds per residue for large single-domain globular proteins.

So how do proteins get around the NP-hard problem of finding the global free energy minimum?

What We Know

-

Transition between any denatured state (e.g. molten globule, random coil) and the native state is much more pronounced than transitions between denatured states

-

Unfolding and folding of discrete protein molecules are reversible processes

-

Unfolding and folding are observed even at the mid-transition (equilibrium) point where the native and unfolded states have equal stability.

-

Transition between the native and any denatured state is “all-or-none” where all alternative structures (e.g. “half-folded” or “misfolded”) are virtually absent, providing a sufficiently high free energy barrier between the native structure and the alternative ones.

The “folding funnel” is widely used to explain protein folding, but it doesn’t solve the paradox per se because there are still too many configurations.

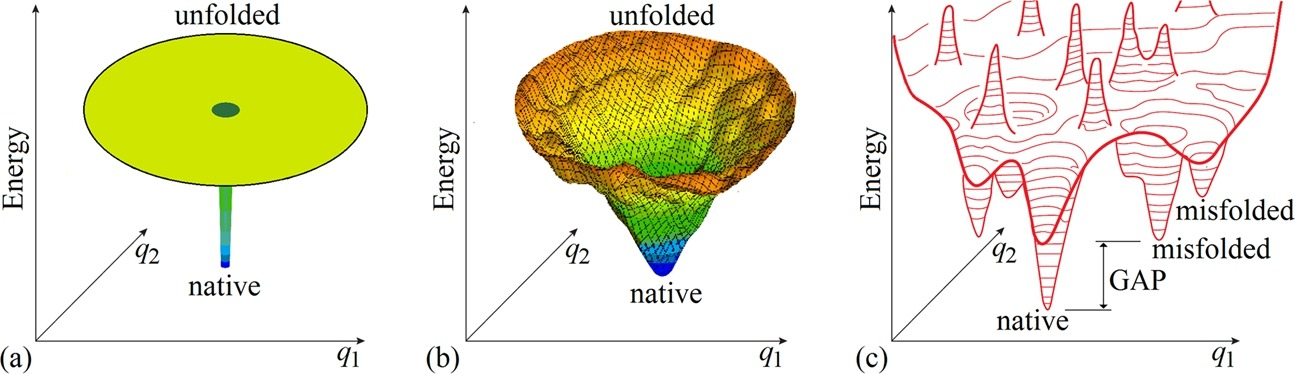

(a) The energy landscape for the “golf course” model, where a protein samples conformations randomly until it hits the “hole” that is the native structure. (b) A general “energy funnel” centering on the protein native structure having the lowest energy. (c) A more detailed general energy landscape with “gap” denoting an free energy gap between the global and other energy minima, necessary to provide the “all-or-none” transition between native and other structures of the chain.

(a) The energy landscape for the “golf course” model, where a protein samples conformations randomly until it hits the “hole” that is the native structure. (b) A general “energy funnel” centering on the protein native structure having the lowest energy. (c) A more detailed general energy landscape with “gap” denoting an free energy gap between the global and other energy minima, necessary to provide the “all-or-none” transition between native and other structures of the chain.

Formation of the protein’s native structure decreases both the chain entropy (increasing the chain’s ordering) and its energy (due to formation of contacts stabilising the lowest-energy fold). The former increases and the latter decreases free energy of the chain.

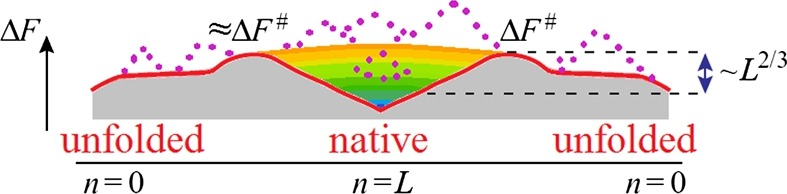

How entropy converts the energy funnel into a “volcano-shaped” free-energy folding landscape with free-energy barriers on each pathway leading from an unfolded conformation to the native fold.

How entropy converts the energy funnel into a “volcano-shaped” free-energy folding landscape with free-energy barriers on each pathway leading from an unfolded conformation to the native fold.

-

Any pathway from the unfolded state to the native one first goes uphill, and only then, from the barrier (i.e., crater edge), descends into the “free-energy funnel”.

-

The smooth free energy landscape corresponds to compact semi-folded intermediate structures

-

The rocks (denoted by dotted lines) present a landscape including non-compact semi-folded intermediate structures.

Protein folding does not occur in one step. An L-residue chain can, in principle, attain its lowest-energy fold in L steps, each adding one fixed residue to the growing structure. Proteins spend most of their folding time, nearly 96% in some cases, waiting in various intermediate conformational states (local thermodynamic free energy minimum) to climb up the free energy barrier and falling back, rather than on moving along the folding pathway.

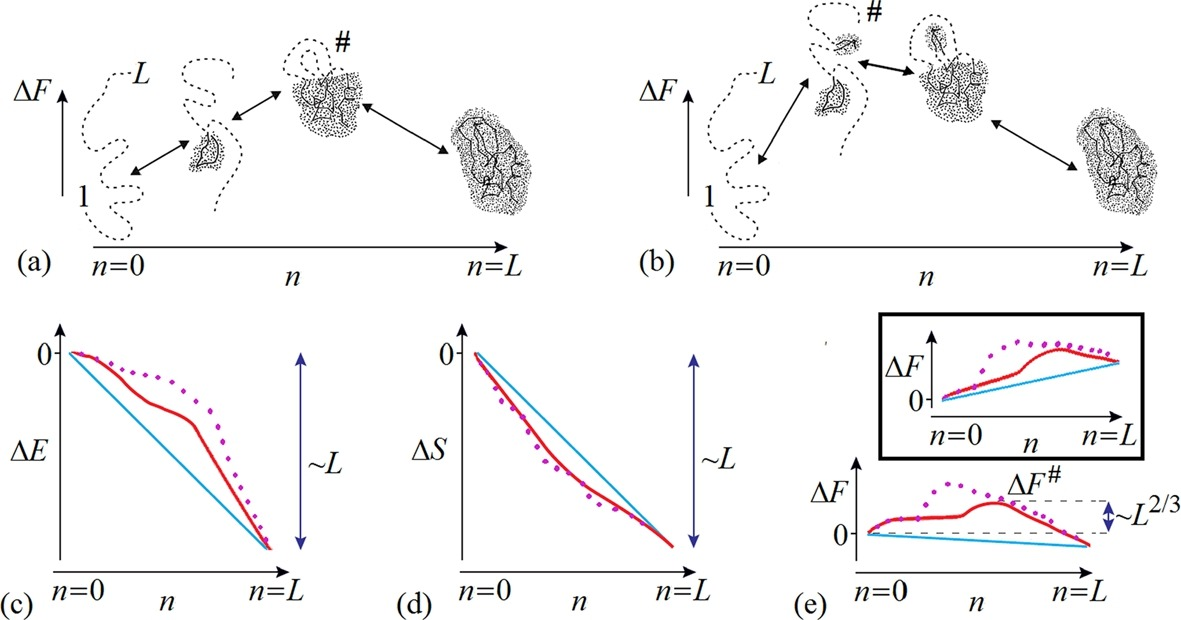

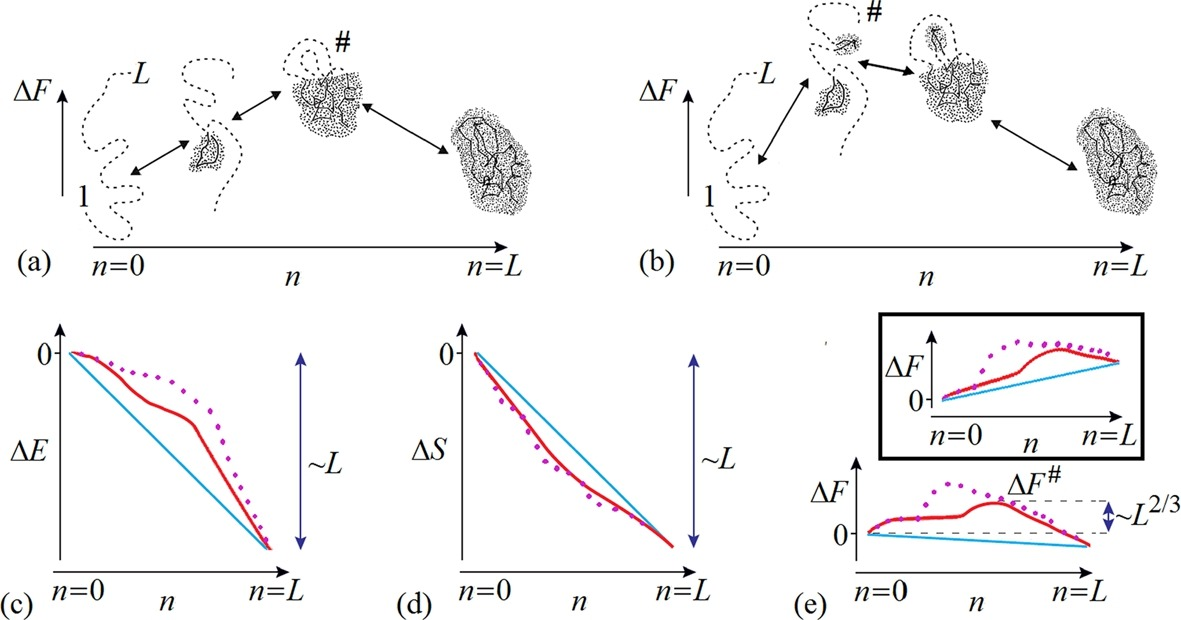

Sequential folding/unfolding between the unfolded random coil (n = 0) and the final structure (n = L) with (a) compact and (b) non-compact semi-folded intermediates.

Sequential folding/unfolding between the unfolded random coil (n = 0) and the final structure (n = L) with (a) compact and (b) non-compact semi-folded intermediates.

Unfolding The Steps

We can look at unfolding because it is easier to outline a good unfolding pathway of any structure than a good folding pathway leading to the lowest-energy fold, while the free energy barrier at both pathways is the same. It is worth mentioning that the unfolding-based estimate gives both the upper and lower estimates of the folding time, while the folding-based estimate gives its upper limit only.

The change of (c) energy ΔE(n), (d) entropy ΔS(n) and (e) free energy ΔF(n) during folding/unfolding.

The change of (c) energy ΔE(n), (d) entropy ΔS(n) and (e) free energy ΔF(n) during folding/unfolding.

-

The full energy ΔE(L) and entropy changes ΔS(L) are approximately proportional to L.

-

The straight blue lines show the linear (proportional to the number of residues already folded n) parts of ΔE(n) and ΔS(n).

-

The red lines show the non-linear parts of ΔE(n) and ΔS(n) (solid lines: with compact intermediate structures; dotted lines: with non-compact intermediates).

At the beginning of folding, the energy decrease is a bit slower because the contact of a newly joined residue with the surface of a small globule is, on average, smaller than its contact with the surface of a large globule. Hence, the maximal deviations of the ΔE(n) and ΔS(n) values from linear dependencies are proportional to only L2/3 instead of L. As a result, ΔF(n)=ΔE(n)−TΔS(n) also deviates from the linear dependence by a value of only ~L2/3 for compact intermediate structures.

Thus, at the equilibrium point (where ΔF(0)=ΔF(L)), the maximal on this pathway free energy excess ΔF over the blue free energy baseline, i.e. the the free energy barrier, is also proportional to only L2/3 for compact intermediate structures.

The time of folding/unfolding of the most native structure do not grow according to Levinthal because (i) during folding, the entropy decrease is almost immediately and almost completely compensated for by an energy decrease along the sequential folding pathway (and, likewise, the energy increase is almost immediately and almost completely compensated for by an entropy increase along the same sequential unfolding pathway), and (ii) the free energy results only from surface effects which are relatively weak.

Hence, the estimated time of folding/unfolding of the most native structure mid-transition is given by 10ns × exp[(1±0.5)L2/3]. It shows that a chain of L ≲ 80-90 residues will find its most stable fold within minutes (or faster) even under “non-biological” mid-transition conditions, where folding is known to be the slowest.

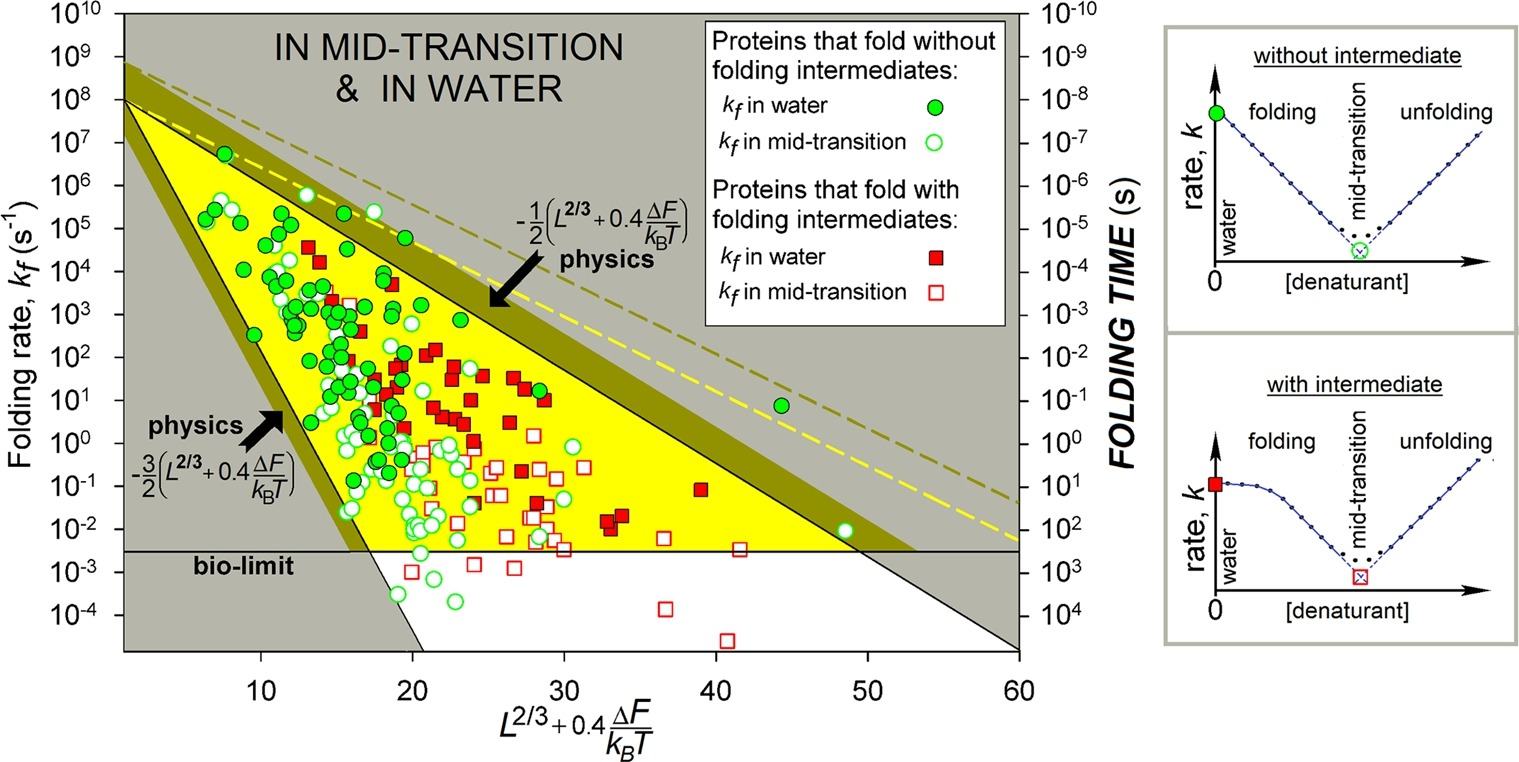

Experimentally measured in vitro folding rate constants in water and at mid-transition for 107 single-domain proteins (or separate domains) without SS bonds and covalently bound ligands.

Experimentally measured in vitro folding rate constants in water and at mid-transition for 107 single-domain proteins (or separate domains) without SS bonds and covalently bound ligands.

Narrowing Scale

Importantly, the protein doesn’t actually have to sample all configurations; it just needs to sample all local energy minima, similar to the idea that a 100-residue protein only needs to find the native topomer (the set of all structures similar to the native structure) in 2 stages of (i) topomer diffusion: random, diffusive sampling of the 3 × 107 distinct topomers to find the native topomer (~0.1 s), followed by (ii) intratopomer ordering: nonrandom, local conformational rearrangements within the native topomer to settle into the precise native state.

Coupled with the observation that most of the interactions of the protein chain are connecting secondary structures, we can estimate the conformation space to scale no faster than ~LN where N is the number of secondary structures (which is much smaller than L), while Levinthal’s estimate scales up at the rate of ~3L.

Conclusion

In sum, Levinthal’s paradox is solved for protein shorter than 100 amino acid residues (provided sequences of these chains ensure a significant stability to only one of their folds); this is because (i) these chains can overcome free energy barriers at the pathway to their most stable folds, independently of their complexity, and (ii) they are able to sample all their folds at the level of secondary structure formation and assembly and find the most stable one.