Mostly rehash of Gwern’s commentary on recent AI progress.

The best answer to the question, “Will computers ever be as smart as humans?” is probably “Yes, but only briefly.”

- Vernor Vinge

The release of GPT-3 two years ago marked the arrival of relatively narrow or “weak” artifical general intelligence (AGI).

In just the past two months, ever larger AI models demonstrate the blessing of scale, where simply scaling existing architecture vaporises problems thought to be inherent to simple architectures, and “learns” new cognitive abilities believed to require bespoke, complicated architectures, without being programmed to learn them. As we ride this exponential, we will only continue to be surprised by the intelligence and generality of each bigger model.

Right now, AI is already better than most of humanity in producing prose, poetry, and programmes; better than most of humanity in casual thinking. Per William Gibson, the future is already here — it’s just not evenly distributed. Hard problems are easy and the easy problems are hard. The artist is made obsolete before the bricklayer, right in front of our eyes.

The blessing of scale suggests that merely throwing more computing power into training AI models will produce machine superintelligence that can beat any human and the entire human civilisation at all congnitive tasks. Just as it’s impossible for Magnus Carlsen to beat any chess engine, it will be impossible for any of us to beat superhuman AGI.

We’re all gonna die.

- GPT-3 And The Blessings of Scale

- Pretraining And The Scaling Hypothesis

- Slowly At First, Then All At Once

- Technological Unemployment Is Already Here

- Frankfurtian Bullshit In A Post-GPT-3 World

- The Singularity Is Nigh

- Conclusion

- Additional Readings

- Endnotes

GPT-3 And The Blessings of Scale

In May 2020, OpenAI announced GPT-3, an unsupervised deep learning transformer-based language model trained on Internet text for the single purpose of predicting the next word in a sentence. It’s the 117x larger 175B-parameter successor to GPT-2, which itself surprised everyone with its ability to learn question answering, reading comprehension, summarisation, and translation, all from the raw text using no task-specific training data. Image GPT, the same exact model trained on pixel sequences instead of text, could generate coherent image completions and samples. GPT-3 astounded everyone — instead of running into diminishing or negative returns, the vast increase in size didn’t merely translate into quantitative improvements in language tasks but also qualitatively distinct improvements that implies meta-learning (attention mechanism as “fast weights” that “learnt to learn”), such as:

- Basic arithmetics

- Creative fiction (poetry, puns, literary parodies, storytelling) e.g. fine-tuned version powered AI Dungeon capable of generating cohesive space operas with almost no editing

- Automatic code generation from natural language descriptions e.g. building a functional React app

- Almost passing a coding phone screen to land a software engineering job

GPT-3 is the first AI system that has obvious, immediate, transformative economic value:

- OpenAI API: GPT-3-as-a-service (from January 2022 onwards the safer, more helpful, more aligned 1.3B-parameter InstructGPT capable of brainstorming, summarising main claims, and analogizing) that powers hundreds of applications

- Codex (GPT-3 trained on GitHub code) powers their programming autocompletion tool GitHub Copilot

GPT-3 demonstrates the blessings of scale: for deep learning, hard problems are easier to solve than easy problems — everything gets better as models get larger (in contrast to the usual outcome in research, where small things are hard and large things impossible). The Bitter Lesson goes:

The biggest lesson that can be read from 70 years of AI research is that general methods that leverage computation are ultimately the most effective, and by a large margin. The ultimate reason for this is Moore’s law, or rather its generalization of continued exponentially falling cost per unit of computation.

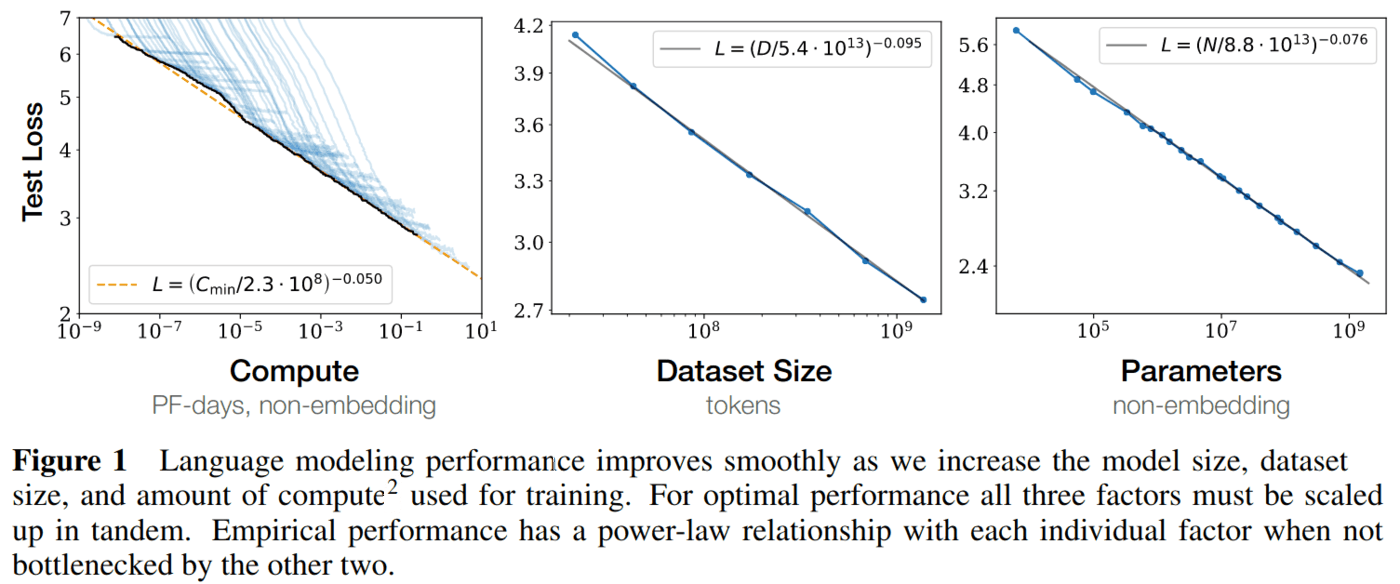

The scaling laws of deep learning, highly consistent over more than 6 orders of magnitude, is driven by neural networks (NNs) functioning as ensembles of many sub-networks that average out to an Occam’s razor, which for small data and models, learn superficial or memorised parts of the data, but can be forced into true learning with hard and rich enough problems. As meta-learners learn amortised Bayesian inference, they build in informative priors when trained over many tasks, and become dramatically more sample-efficient and better at generalisation.

Once the compute is ready, the paradigm will appear:

As Gwern writes, GPT-3 is terrifying because it is a tiny model compared to what’s possible, trained in the dumbest way possible on a single impoverished modality on tiny data, sampled in a dumb way, its benchmark performance sabotaged by bad prompts and data encoding problems, and yet the first version already manifests crazy runtime meta-learning — and the scaling curves still are not bending!

Per OpenAI’s Kaplan et al. 2020, the leaps we have seen over the past few years are not even halfway there in terms of absolute likelihood loss:

GPT-3 represents ~10^3 — plenty of room for further loss decreases.

If we see such striking gains in halving the validation loss from GPT-2 to GPT-3 but with so far left to go, what is left to emerge as we halve again?

Pretraining And The Scaling Hypothesis

The pretraining thesis goes:

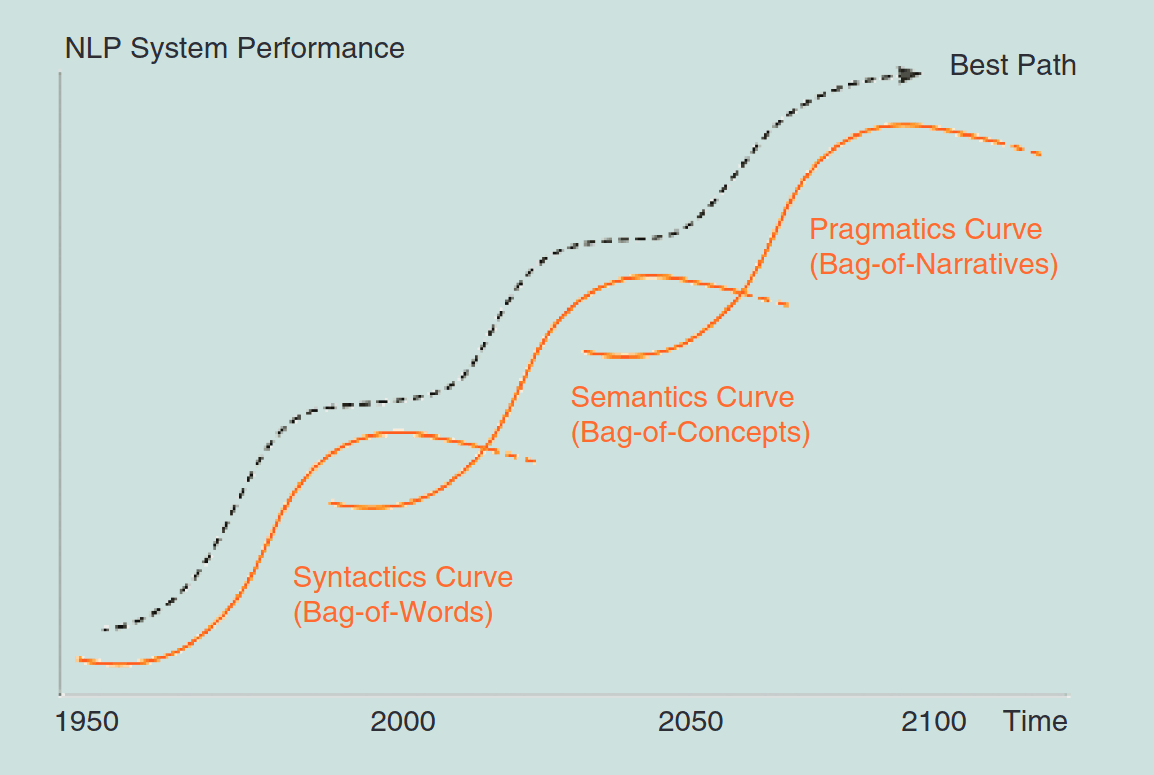

Humans are the cyanobacteria of AI: we emit large amounts of structured data in which logic, causality, object permanence, history are encoded. A model like GPT-3 trains on such data in which “intelligence” is implicit, and learns from the crudest level:

- Some letters are more frequent than others (alphanumeric gibberish): 8-5 bit error per character

- Words and punctuations exist (still gibberish): 4-3 bit error per character

- Words “cluster” (bag of words): <3 bit error per character

-

Sentences exist (starts making sense): 2 bit error per character (every additional 0.1 bit decrease starts to come more costly1)

- Grammar exists e.g. keeping pronouns consistent (multiple sentences make sense): 1-2 bit bit error per character

- Subtleties e.g. solving repetition loops (paragraphs make sense) <0.02 bit error per character

Language model performance can be measured by how many bits it takes to convey a character i.e. bits per character (BPC): GPT-2 had a cross-entropy WebText validation loss of ~3.3 BPC; GPT-3 halved that loss to ~1.73 BPC. For a hypothetical GPT-4, if the scaling curve continues for another 3 orders or so of compute (100–1000x) before hitting harder diminishing returns, the cross-entropy loss will drop to ~1.24 BPC.

It still won’t be near the natural language performance of humans who (in ASCII) use a byte to express a full 7 bits of information i.e. Shannon’s 7-gram character entropy (0.7 BPC).

What is in that missing >0.4 BPC? Everything! While random babbling sufficed at the start, nothing short of true understanding will suffice for ideal prediction. The last bits are deepest. Analogous to humans: we all perform everyday actions like buttoning our shirts well given enough practice and feedback, but we differ when we run into the long tail of choices that are:

- Novel

- Rare

- Short in execution but unfold over a lifetime

- Without any feedback (e.g. after our death)

One only has to make a single bad decision to fall into ruin. A small absolute average improvement in decision quality can be far more important than its quantity indicates, hence why the last bits are the hardest and deepest.

If GPT-3 gained so much meta-learning and world knowledge by dropping its absolute loss 50% when starting from GPT-2’s level, what capabilities would another 30% improvement over GPT-3 gain? If we trained a model which reached that loss of 0.7 i.e. predict text indistinguishable from a human, how could we say that it doesn’t truly understand everything2?

Thus, the scaling hypothesis: the blessings of scale as the secret of artificial general intelligence (AGI) — intelligence is “just” simple NNs applied to diverse experiences at a (currently) unreachable scale; as increasing computational resources permit running such algorithms at the necessary scale, NNs will get ever more intelligent.

Slowly At First, Then All At Once

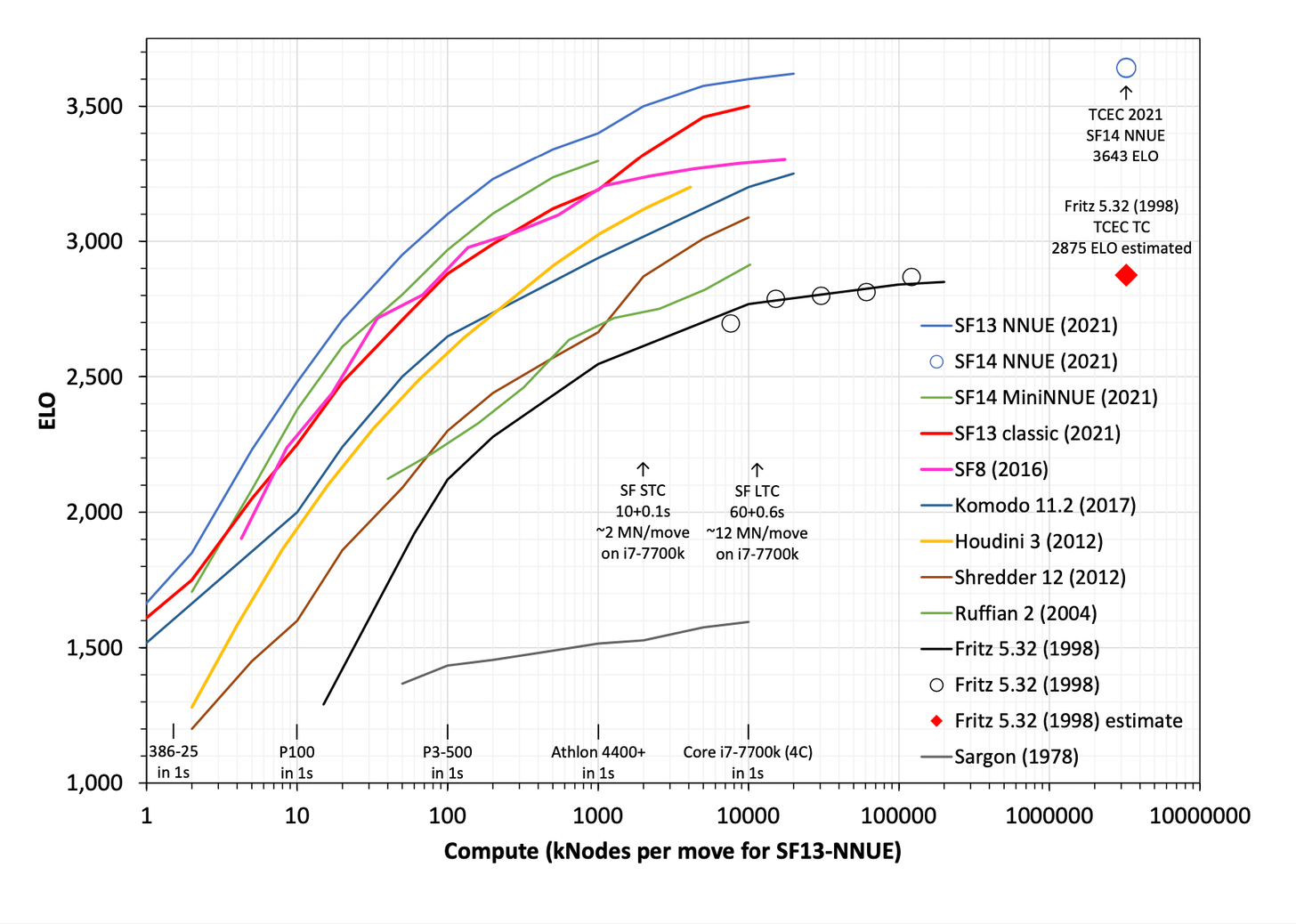

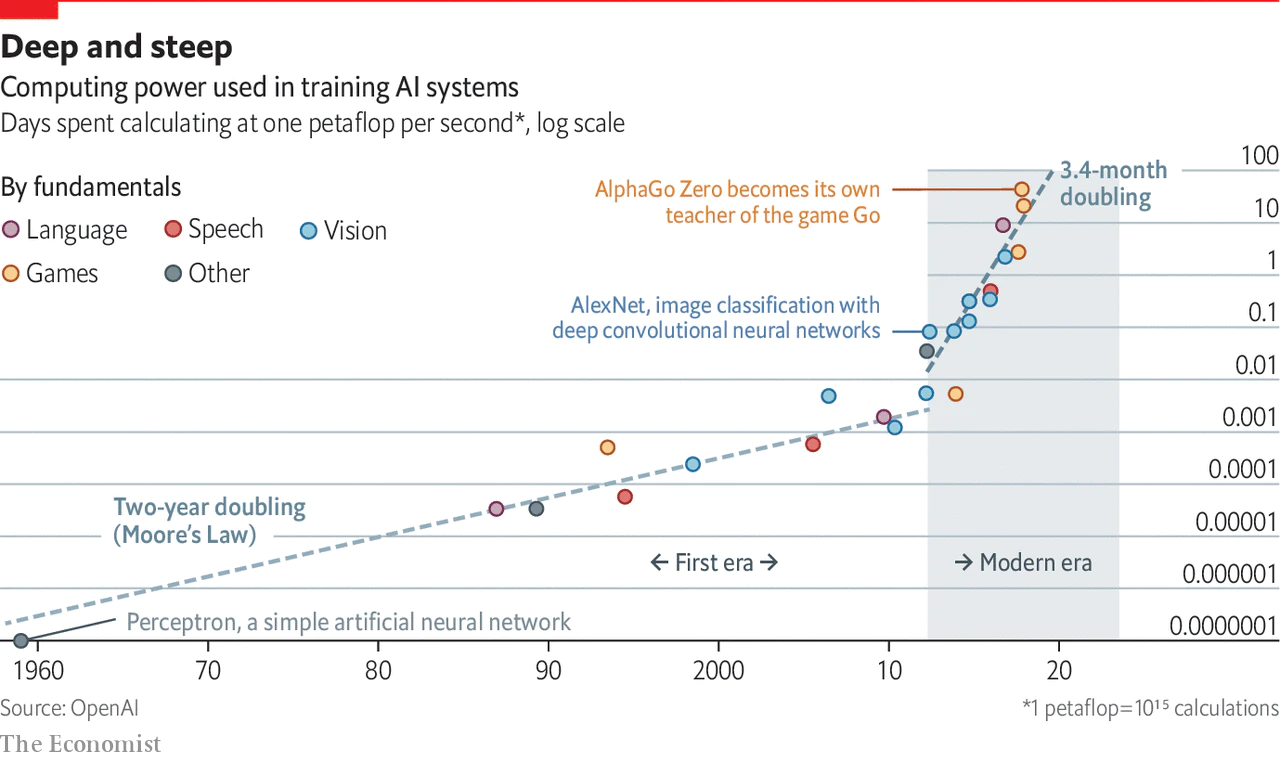

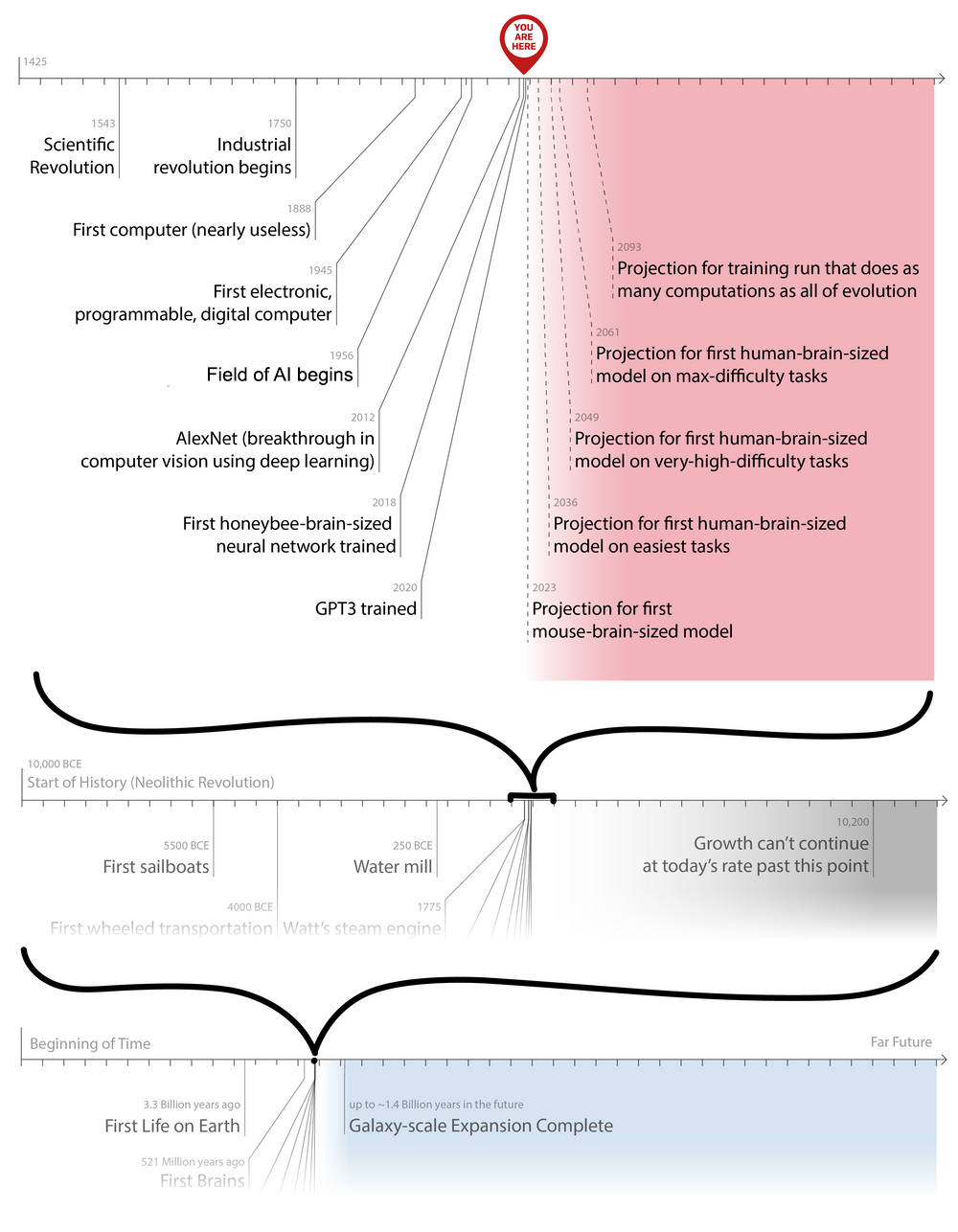

The deep learning revolution started with AlexNet in 2012. Since then, computing power used in training AI systems has been doubling every 3.4 months:

Even in 2015, the scaling hypothesis seemed highly dubious — you needed something to scale, after all, and it was all too easy to imagine flaws in existing systems would never go away, and progress would sigmoid any month now. Like the genomics revolution where a few far-sighted seers extrapolated that the necessary n for GWASes would increase exponentially and deliver powerful polygenic scores soon (which I wrote about), while sober experts wrung their hands over “missing heritability” and the miraculous complexity of biology to scoff about how such n requirements proved GWAS was a failed paradigm, the future arrived at first slowly and then quickly.

For a while after GPT-3 was published, we were possibly in hardware overhang where large quantities of compute can be diverted to running powerful AI systems as soon as the software is developed (so as one powerful AI system exists, probably a large number of them do). Google Brain was entirely too practical and short-term; DeepMind believes that AGI will require effectively replicating the human brain module by module; OpenAI, lacking anything like DeepMind’s Google cashflow or its enormous headcount is making a startup-like bet that they know an important truth that is a Thielian secret: the Scaling Hypothesis is true.

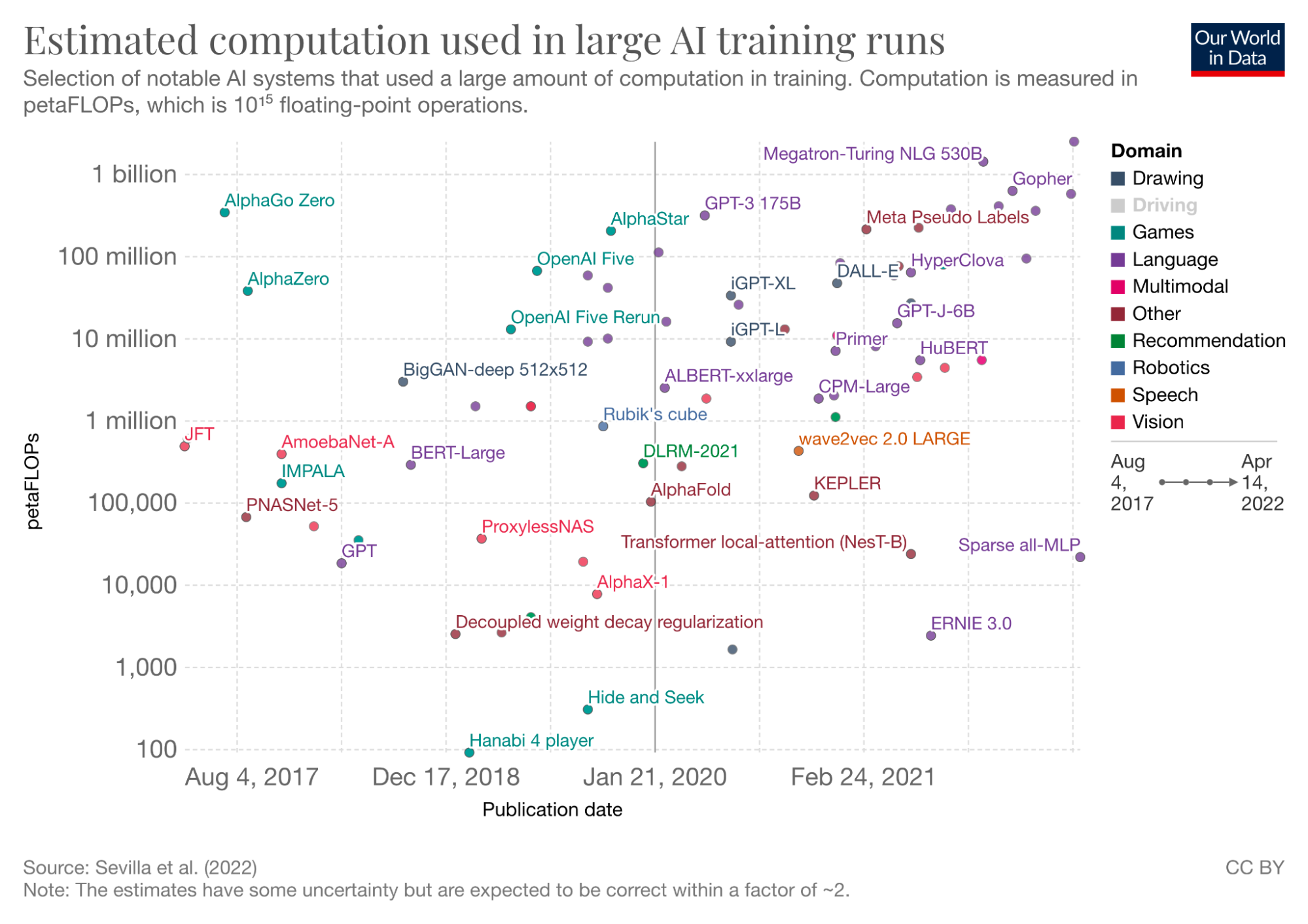

In August 2021, Stanford’s entire AI department released a 200-page 100-author neural scaling laws manifesto announcing their pivot to position themselves as the number one at academic ML scaling research. Only recently do we see Google AI, Google Brain, and DeepMind treat GPT-3 as scaling’s Sputnik moment:

Google’s 540 billion parameter PaLM is the right-most, up-most dot.

In just the past two months, we saw bigger and bigger models like DeepMind’s 80B-parameter Flamingo (paper), Robotics at Google and Everyday Robots (also Alphabet-owned)’s SayCan (paper), and Robotics at Google’s Socratic Models (paper). Below I highlight the most blockbusting five. Again, it’s just the past two months!

Google AI’s 540B-parameter PaLM

Continues the Kaplan scaling, sees discontinuous improvements from model scale (see comparison with GPT-3). The surprise is perhaps how poor the communication between Google and DeepMind is, as you will see.

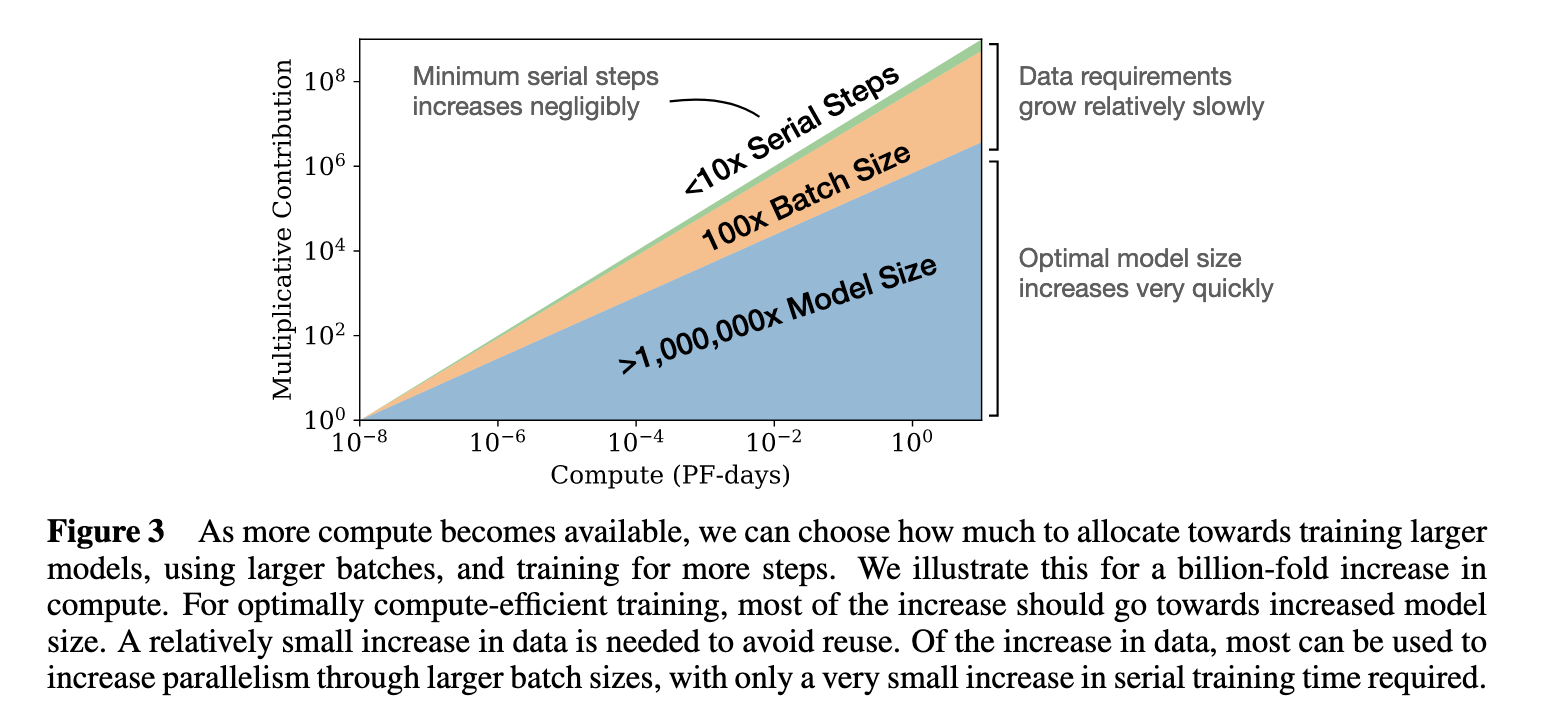

DeepMind’s 70B-parameter Chinchilla

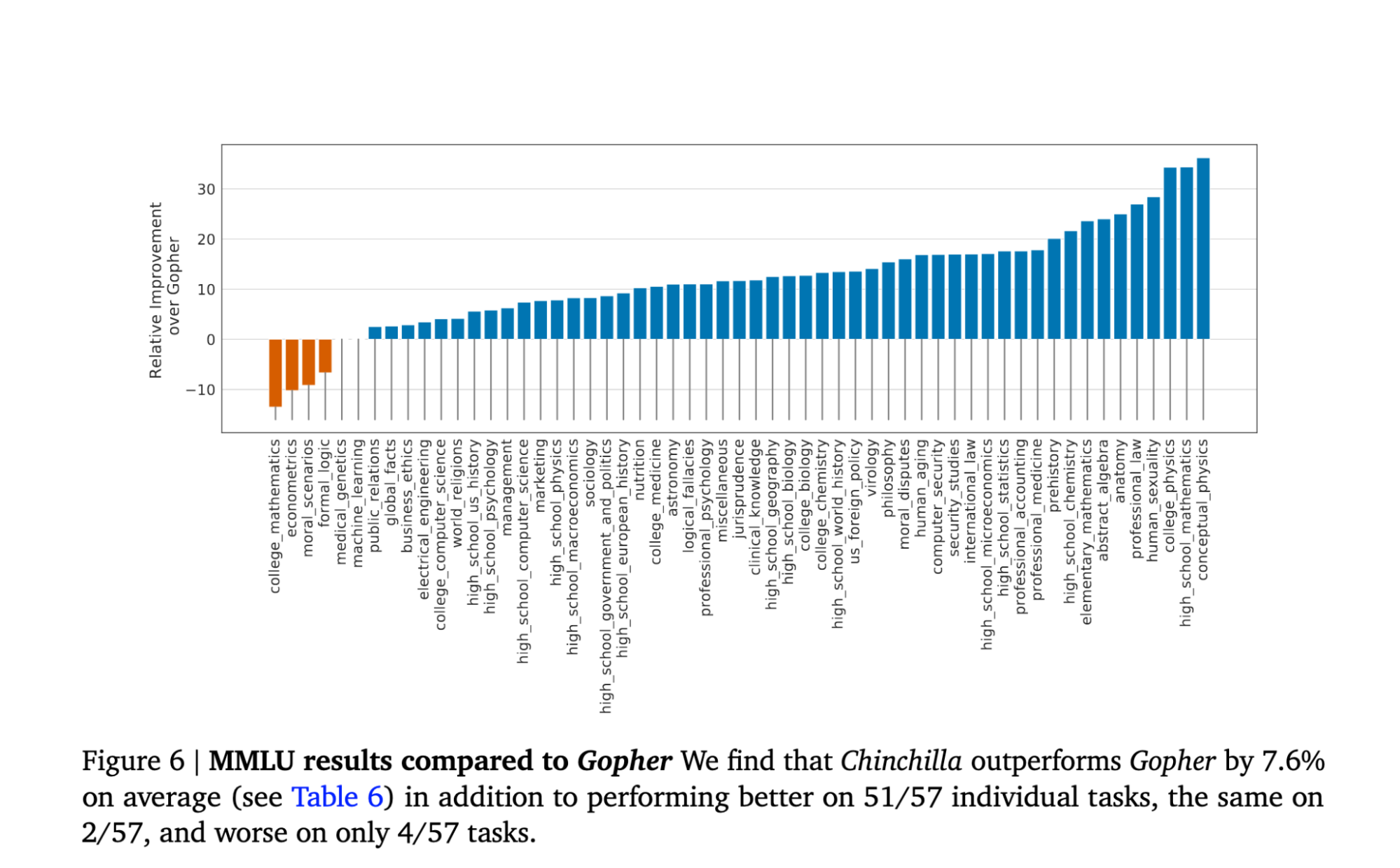

Outperforms the much larger 175B-parameter GPT-3 and DeepMind’s own 280B-parameter Gopher, demonstrating that essentially everyone has been training LLMs with a deeply suboptimal use of compute.

Model size is (almost) everything.

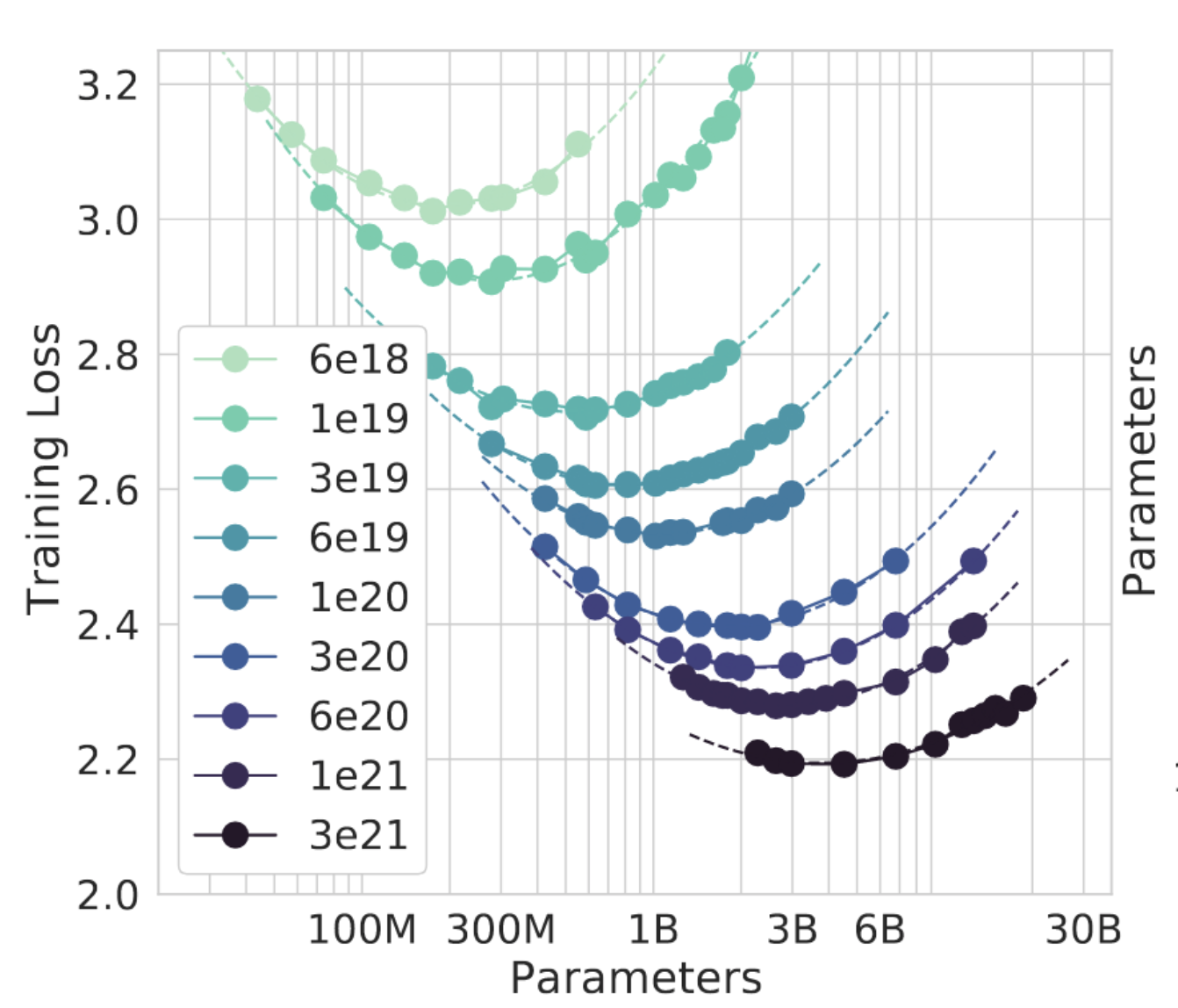

DeepMind chose 9 quantities of compute (1018-1021 FLOPs) and trained many different-sized models at each quantity:

The best models are at the minima.

Connecting the minima at each curve gives you a new scaling law: for every increase in compute, data and model sizes should increase by the same amount. DeepMind verified the new training law by training the 70B-parameter Chinchilla using the same compute used for their own 280B-parameter Gopher i.e. Chinchilla trained with 1.4 trillion tokens compared to Gopher’s 300 billion tokens. Indeed, Chinchilla outperforms Gopher by 7.6% on average:

This implies that we shouldn’t see models larger than the 540B-parameter PaLM trained on 780B tokens for a while — it doesn’t make sense until we have 60x as much compute as was used for Gopher/Chinchilla (which is why it is surprising DeepMind let Google piss away millions of dollars in TPU time).

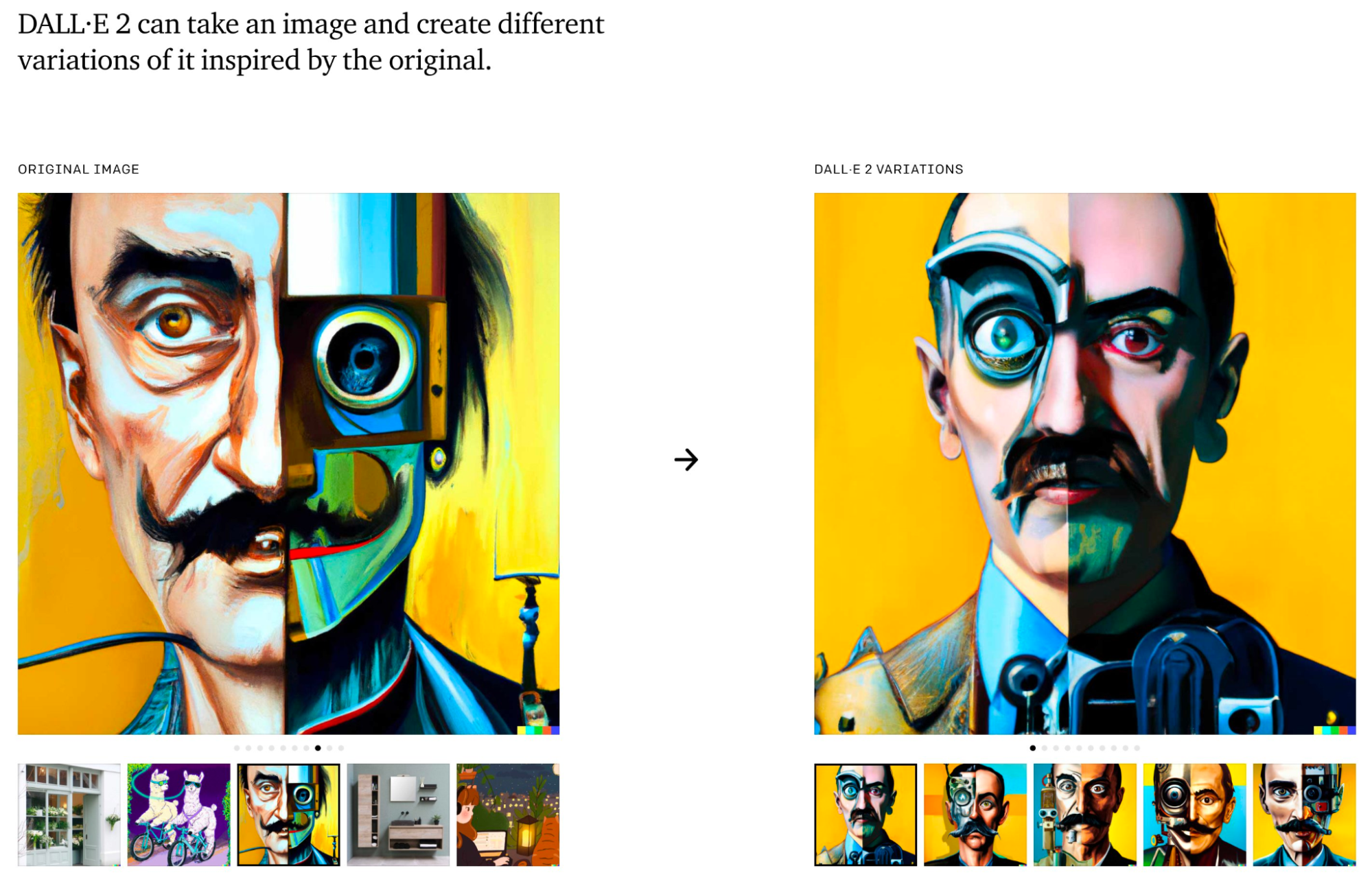

OpenAI’s 3.5B-parameter DALL·E 2

Successor to the 12B-parameter DALL·E (an implementation of GPT-3 trained on text-image pairs from the Internet). Improvements mainly due to algorithmic innovation (not scaling). The examples are stunning:

- Kermit in style of different movies/TV shows

- Physical artwork

- Playing with DALL·E 2

- What DALL-E 2 can and cannot do

DALL·E 2 struggles with anime, realistic faces, text in images, multiple subjects arranged in complex ways, and editing. How many of these will be solved by throwing more compute and training data at them? The scaling curves still haven’t bent, and no one has tried diffusion models’ scaling law on better hyperparameterised models like Chinchilla yet.

The text in image problem3 is probably due to an obscure technical detail that also plagued GPT-3 performances in rhyming, alliteration, punning, anagrams or permutations, acrostic poems, and arithmetic: the models do not see characters but ~51k word or sub-word-chunks called byte-pair encodings (BPEs). To breakthrough, the models just need to memorise enough of the encrypted number/word representations using tricks like rewriting numbers to individual digits or BPE-dropout to expose all possible tokenizations, or better yet, character-level representations.

Google Brain’s Imagen

Outcompetes DALL·E 2 on text-to-image COCO benchmark despite being smaller than DALL·E 2. The main change appears to be reducing the CLIP reliance in favour of a much larger and more powerful text encoder before doing the image diffusion stuff. They make a point of noting superiority on “compositionality, cardinality, spatial relations, long-form text, rare words, and challenging prompts.” The samples also show text rendering fine inside the images. The results are stunning:

What does this mean for artists? Most AI art criticism comes from a place of not realising that (almost) everyone’s favourite artists are actually curators and not manufacturers. Artists will become more like today’s art directors: people with amazing visual imagination and taste, the ability to see new things, and to help orchestrate it into existence. The net result may be a far more visual culture4. (See also Oxford’s report on AI and the Arts)

In the US, only art created by humans, not AI, can be copyrighted.

When DALL·E 2 can do this to any artwork, what does it mean for copyright?

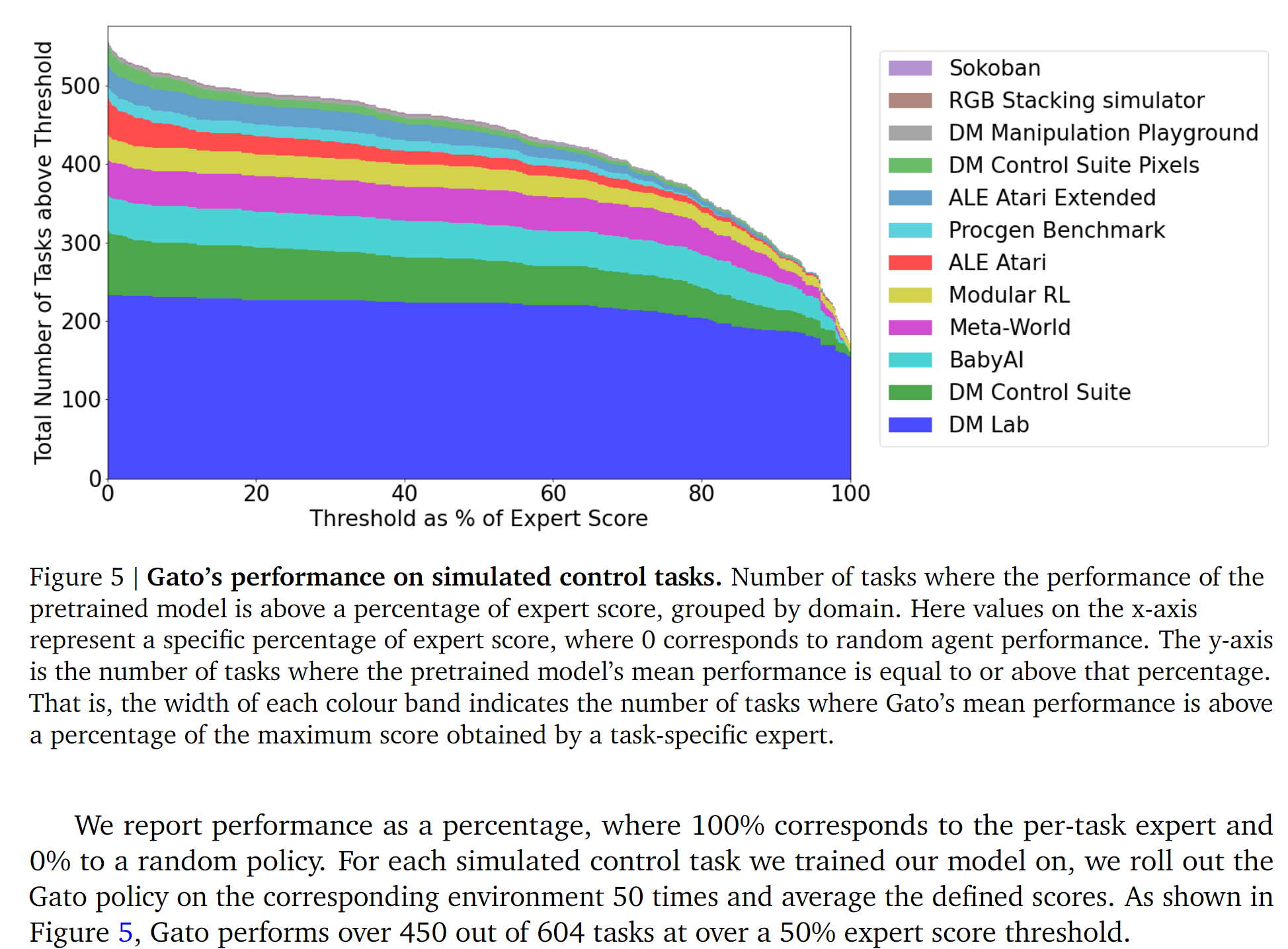

DeepMind’s 1.2B-parameter Gato

Trained for a myriad of tasks like image captioning, engaging in dialogue, stacking blocks with a real robot arm, and playing Atari games, the tiny (1.2B parameters) Gato performs 450 out of 604 taks at over 50% expert score:

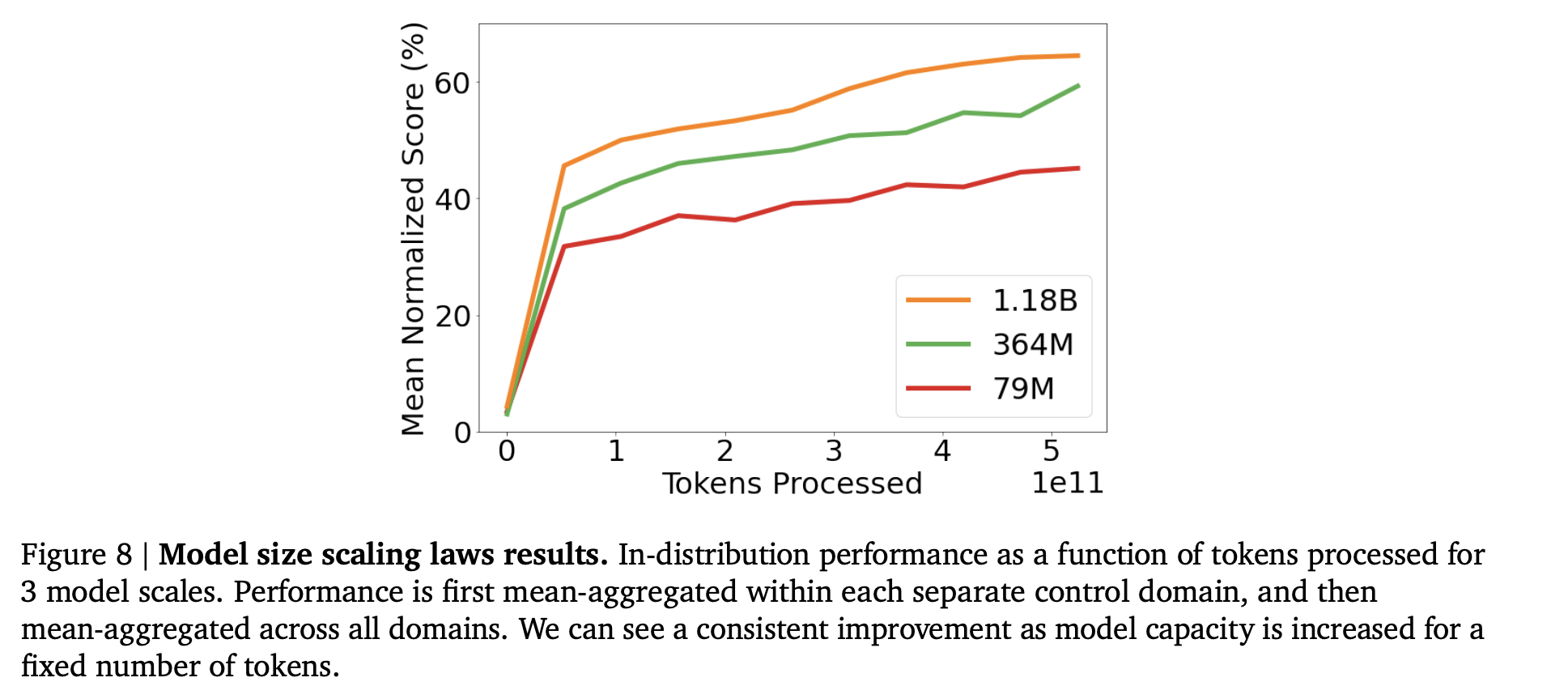

Scaling just works: just train a 1.2B-paramater Transformer on half a thousand different tasks and the scaling curve looks exactly like you’d expect:

Multi-task learning is indeed just another blessing of scale: as DeepMind notes, it used to be that learning multiple Atari games in parallel was really hard; people thought very hard and ran lots of experiments to try to create things like Popart less than 4 years ago where it was a triumph that, due to careful engineering, a single checkpoint could play just the ALE-57 games with mediocre performance.

If one had any doubts, DeepMind is now fully scale-pilled.

We live in a timeline in which the final breakthrough that precipitates AGI could plausibly be literally some one-sentence platitude about general problem-solving — Large Language Models are Zero-Shot Reasoners, Kojima et al. 2022: simply adding “Let’s think step by step” before each answer increases GPT-3 accuracy on MultiArith from 17.7% to state-of-the-art (SOTA) 78.7% and GSM8K from 10.4% to SOTA 40.7%.

Technological Unemployment Is Already Here

Technological unemployment is a very complex issue. Normal people worry about technological unemployment. Economists like Bryan Caplan, Robin Hanson, Tyler Cowen, and Arnold Kling keep telling them to relax, but LLMs since GPT-3 should make them rethink. From AlphaZero, we can see that there is no chance any useful man+machine combination will work together for more than a few years, as humans will soon be a liability only. Humans need not apply.

This time is different: before, the machines began handling brute force tasks and replacing things that offered only brute force and not intelligence like horses or watermills. It’s clear that the machines are now slowly absorbing intelligence — the final province of humans. Machines switched from being complements to being substitutes in some sectors a while ago. Humans need not apply.

During the various panics and busts in the past centuries, there were huge disemployment effects as companies were forced to automate, but the people were able to switch sectors or find new jobs. The trucking industry alone employs 3% of the entire American population, and how many of those employees are skilled operations research PhDs who can easily find employment elsewhere in logistics? Imagine a kid with an IQ of 70, his Ricardian comparative advantage doesn’t guarantee there’s anything worth hiring him for (even laundry has gotten harder). Humans need not apply.

We live in a world where in some cases we would not hire someone at any price. One person in an o-ring process can do an incredible amount of damage if they are only slightly subpar; to continue the NASA analogy, one loose bolt can cost $135 million, one young inexperienced technician can cost $200 million. We just have to calculate the expected-value of reducing the number of such incidents by even 0.01%. Humans need not apply.

Frankfurtian Bullshit In A Post-GPT-3 World

As Sarah Constantin writes, humans who are not concentrating are not general intelligences. Unless you make an effort to to read carefully, you probably cannot detect any mistakes in GPT-3’s nonfiction upon skimming. Try for yourself. Notice how hard you have to pay attention to to pick up any mistakes. In a post-GPT-3 world, can you bring yourself to to read everything with that level of care? How many times have I repeated the word “to” in this paragraph alone without you noticing? What about articles on topics you don’t have any expertise in? GPT-induced Gell-Mann amnesia is going to fry your brain. OpenAI has achieved the ability to pass the Turing test against humans on autopilot.

As Robin Hanson writes, a lot of human speech is just babbling — simply linking words and sentences statistically likely to come after the next, not unlike GPT-3. The median student learns a set of low order correlations, but if you ask an exam question probing a deep structure answer, most students give the wrong answer. These low order correlations also seem sufficient to capture most polite conversation talk (e.g. the weather is nice, how is your mother’s illness, and damn that other political party), inspirational TED talks, and when podcast guests pontificate on topics they really don’t understand (e.g. quantum mechanics, consciousness, postmodernism, or the need always for more regulation everywhere).

What unites the GPT-3 and its cousins is an unflagging enthusiasm to render whatever’s been requested, no matter how absurd or overwrought — they are fundamentally Frankfurtian bullshitters:

The liar cares about the truth and attempts to hide it; the bullshitter doesn’t care if what they say is true or false, but cares only whether the listener is persuaded.

As Venkatesh Rao notes, bullshit in this epistemological sense is not a moral failure, but an incomplete cognition mode. It corresponds to the upstream part of what Daniel Dennett called the “multiple drafts” view of consciousness. First you confabulate, then you discriminate — you free-associate to produce output that has a cosmetic coherence, and then close the truth loop somehow in a downstream discrimination step before actual output. Basically, bullshitters output indiscriminately.

All presentations of AI art include the text prompt — the viewer’s pleasure is not in the image, but in the spectacle of the computer’s interpretation. Hence AI art is a genre unto itself, and the bullshit has not found its footing as “mere” art. As Robin Sloan notes:

That’s the paradox of AI art: it leverages access to the spigot of infinity to produce a sense of scarce invention. In an overstuffed audiovisual landscape, it’s the “AI” and not the “art” that provides a reason to look at this and not that, listen to this and not that.

Just as AI art has no artistic merit until OpenAI solves “taste”, effortful thinking is still out of reach until OpenAI fully embodies complete cognition (the generation + discrimination production pipeline with a truth loop) in GPT-n.

Constantin again:

The mental motion of “I didn’t really parse that paragraph, but sure, whatever, I’ll take the author’s word for it” is, in my introspective experience, absolutely identical to “I didn’t really parse that paragraph because it was bot-generated and didn’t make any sense so I couldn’t possibly have parsed it”, except that in the first case, I assume that the error lies with me rather than the text. This is not a safe assumption in a post-GPT2 world. Instead of “default to humility” (assume that when you don’t understand a passage, the passage is true and you’re just missing something) the ideal mental action in a world full of bots is “default to null” (if you don’t understand a passage, assume you’re in the same epistemic state as if you’d never read it at all.)

The Singularity Is Nigh

The AI neither hates you, nor loves you, but you are made out of atoms that it can use for something else.

- Eliezer Yudkowsky

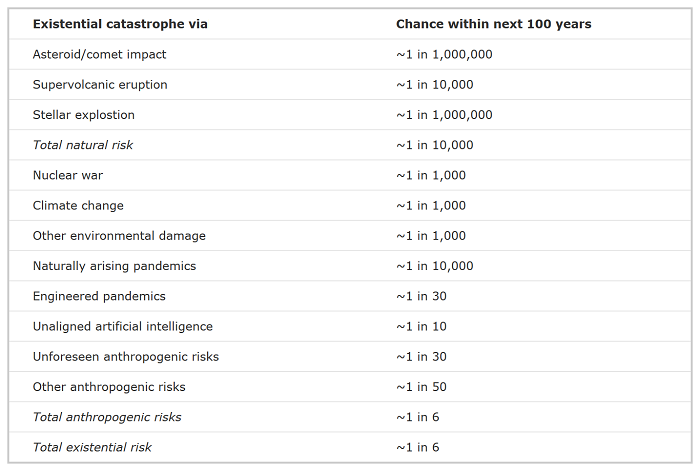

In The Precipice, the definitive book on existential risks, Toby Ord ranks unaligned artificial intelligence as the greatest risk to humanity’s potential in the next century.

Ord explains the high number for such a speculative risk:

A common approach to estimating the chance of an unprecedented event with earth-shaking consequences is to take a sceptical stance: to start with an extremely small probability and only raise it from there when a large amount of hard evidence is presented. But I disagree. Instead, I think that the right method is to start with a probability that reflects our overall impressions, then adjust this in light of the scientific evidence. When there is a lot of evidence, these approaches converge. But when there isn’t, the starting point can matter.

In the case of artificial intelligence, everyone agrees the evidence and arguments are far from watertight, but the question is where does this leave us? Very roughly, my approach is to start with the overall view of the expert community that there is something like a 1 in 2 chance that AI agents capable of outperforming humans in almost every task will be developed in the coming century. And conditional on that happening, we shouldn’t be shocked if these agents that outperform us across the board were to inherit our future.

Read Gwern’s (fictional) It Looks Like You’re Trying To Take Over The World to imagine a hard takeoff scenario using solely known sorts of NN and scaling effects. Then read AGI Ruin: A List of Lethalities in which Eliezer Yudkowsky, for the first time publicly, explains what he spent the last several years doing (and he is pessimistic).

What are some concrete problems in AI safety? Fom Amodei et al. 2016, take a robot that cleans up messes in an office using common cleaning tools as an example:

- Avoiding negative side effects (e.g. ensure robot doesn’t knock over vase to clean faster without manually specifying everything it shouldn’t disturb)

- Avoiding reward hacking (e.g. ensure robot doesn’t disable its vision so it won’t find any mess while rewarding it for a mess-free environment)

- Scalable oversight (e.g. ensure robot doesn’t throw away phone but does candy wrapper without having to ask the humans every time)

- Safe exploration (e.g. ensure robot doesn’t put a wet mop in an electrical outlet while allowing it to experiment with mopping strategies)

- Robustness to distributional shift (e.g. ensure robot learns that its cleaning strategies for an office might be dangerous on a factory workfloor)

The explainable ML community and AI safety is nowadays an eminently empirical field centred around understanding the kinds of models, like transformers, that seem promising, and trying to devise new ways to train them that lead to desired behaviours, for example trying to get language models to output benign completions to a given prompt. There’s more tool building, more concrete tractable problems and less theorising about arbitrarily general intelligent systems.

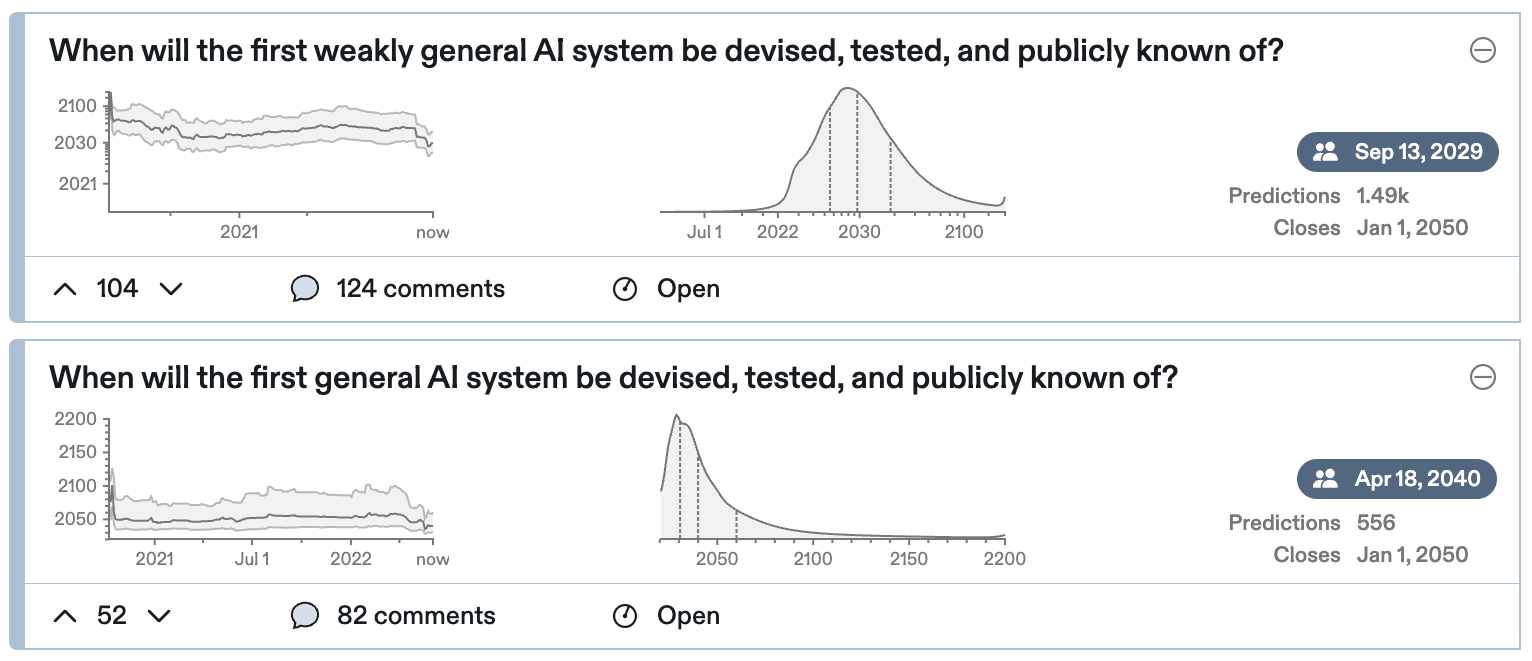

AI timeline

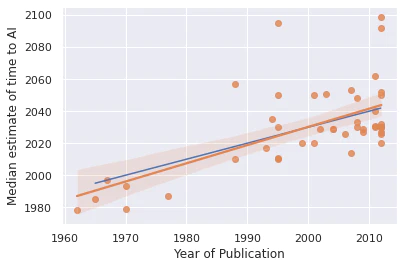

Is AI Progress Impossible To Predict? AI has improved on a task recently gives us exactly zero predictive power for how much the next model will improve on the same task. Moore’s Law giveth, Platt’s Law taketh away: any AI forecast will forecast strong AI to be 30 years out:

Platt’s Law in blue, OLS regression line in orange; the median forecast is 25 years out.

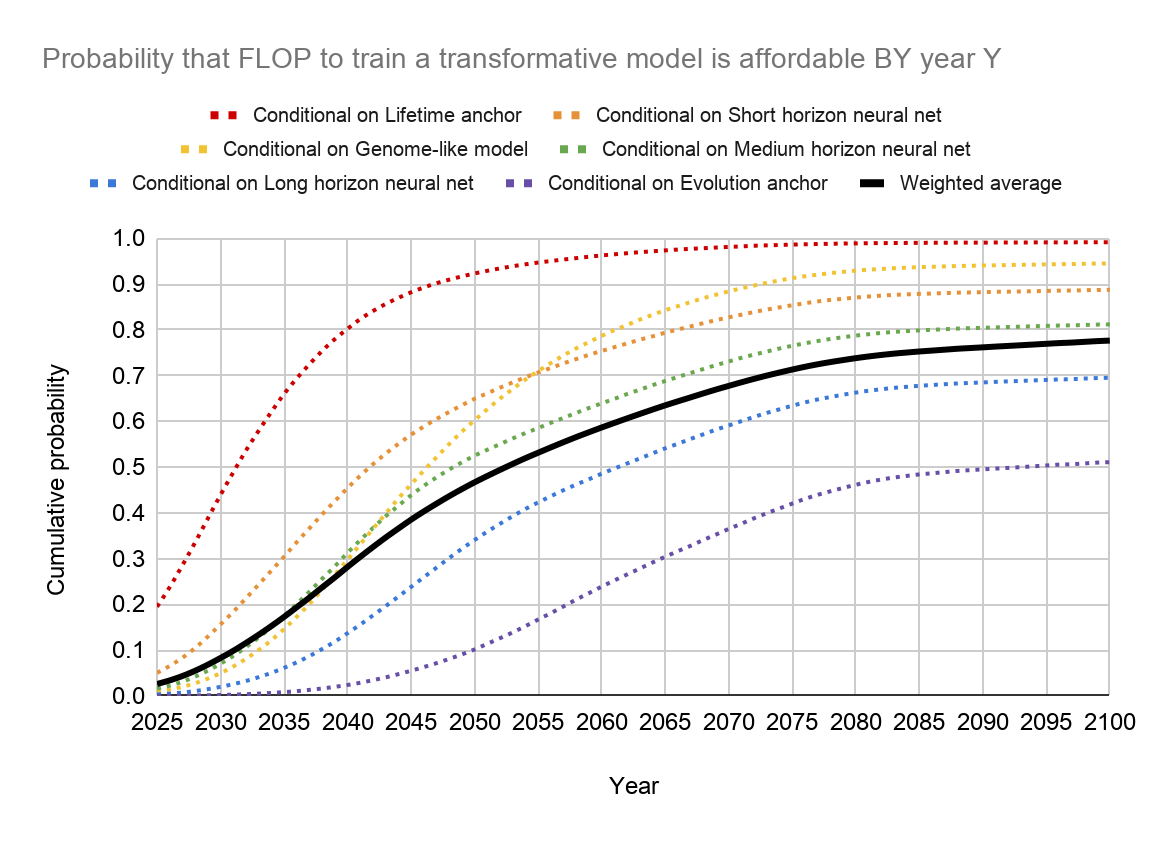

Nevertheless, the average 50% prediction clusters around 2040-60. Holden Karnofsky predicts more than a 10% chance of PASTA (Process for Automating Scientific and Technological Advancement) transformative AI (see also burden of proof and where the arguments and “experts” stand) : >10% probability by 2036; a 50% by 2060; and a 66% by 2100.

- OpenPhil’s Report on Semi-informative Priors predicts: 8% by 2036; 13% by 2060; 20% by 2100

- Grace et al. 2018 surveyed 352 AI researchers at the 2015 NIPS and ICML (the premier) conferences: 20% probability by 2036; 50% by 2060; 70% by 2100.

- Richard Sutton of The Bitter Lesson fame predicts 50% probability of Human-Level AI by 2040.

- Ajeya Cotra’s Report on Biological Anchors (summaries by Scott Alexander, Holden Karnofsky, Rohin Shah)” predicting arrival of transformative AI: >10% probability by 2036; 50% chance by 2055; 80% chance by 2100

FLOPs alone turn the wheel of history.

Cotra’s report reminds Scott Alexander of an old joke:

An astronomy professor says that the sun will explode in five billion years, and sees a student visibly freaking out. She asks the student what’s so scary about the sun exploding in five billion years. The student sighs with relief: “Oh, thank God! I thought you’d said five million years!”

You can imagine the opposite joke: A professor says the sun will explode in five minutes, sees a student visibly freaking out, and repeats her claim. The student, visibly relieved: “Oh, thank God! I thought you’d said five seconds.”

In all the AGI timeline predictions, the professor is saying the sun will explode in five minutes instead of five seconds. Compared to the alternative, it’s good news. But if it makes you feel complacent, then the joke’s on you.

Conclusion

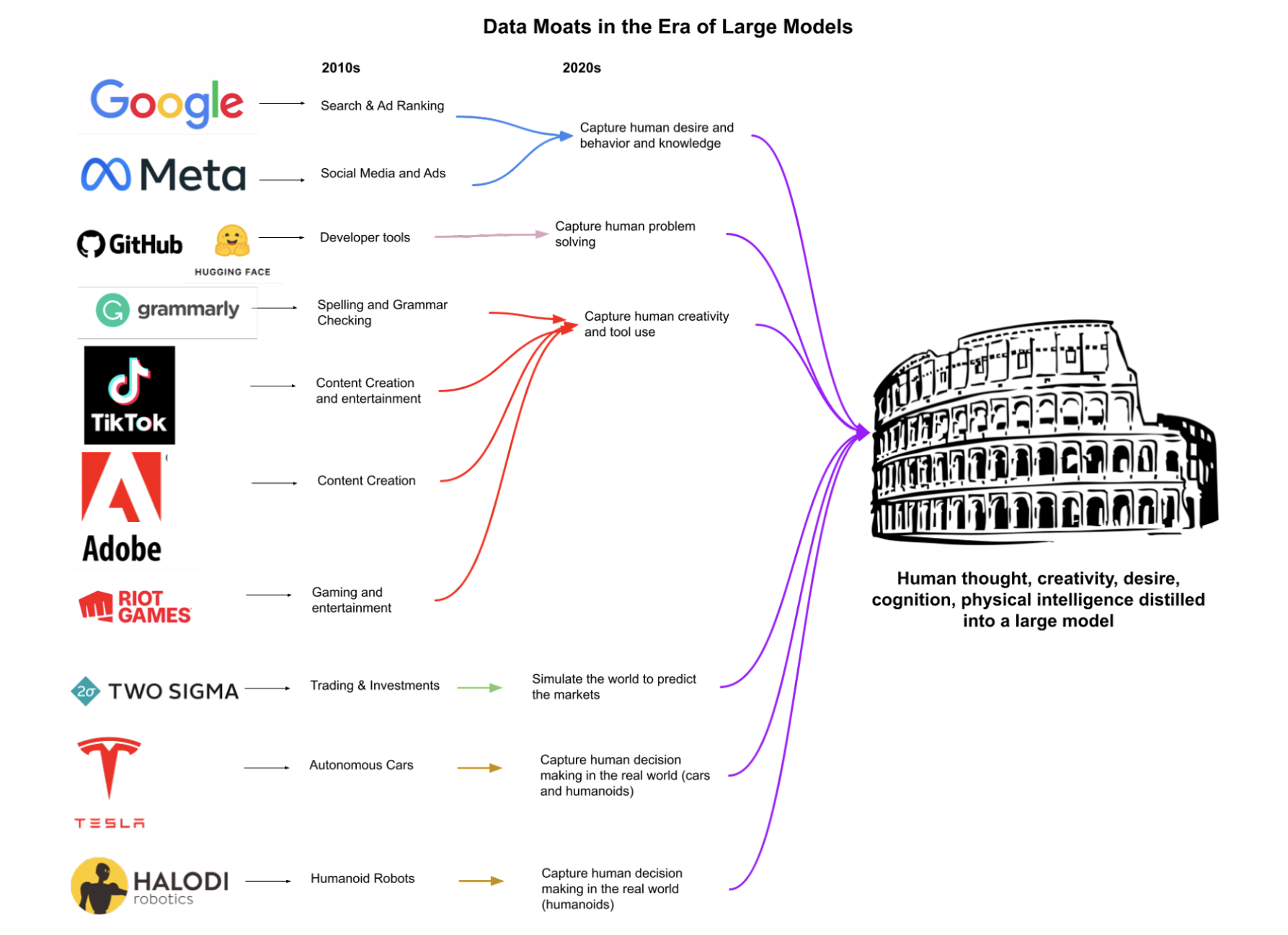

As Kaplan notes, all products for creators will have embedded intelligence from LLMs (Copilot in VSCode, DALL·E 2 in Photoshop, GPT-3 in Google Docs); these companies will need to roll their own LLMs or pay a tax to OpenAI/DeepMind/Google.

If you actually believe in AI risk, you should vote with your feet and work on AI safety. If you don’t, you should still pivot your career to work on AI as every successful tech company will use their data moats to build some variant of AGI.

All tech problems are ultimately AGI-complete.

It is up to you to immanentize the eschaton.

Additional Readings

ML Intro

- Jay Alammar: A Visual and Interactive Guide to the Basics of Neural Networks

- Machine Learning for Everyone

- Google AI: education

- A Neural Network in 11 lines of Python part 1, part 2

- Beginner’s Guide to Understanding CNN

- Jason Mayes: Machine Learning 101 (deck)

ML Books

- Michael Nielsen: Neural Networks and Deep Learning

- Ian Goodfellow: Deep Learning Book

- Maths Basics for Computer Science and Machine Learning

- Grokking Deep Learning

- Introduction to Machine Learning Interviews

- Top Machine Learning Books recommended by experts (2022 Edition)

ML Courses

- Andrew Ng: Stanford ML Syllabus, Coursera, Python assignments

- deeplearning.ai: Deep Learning

- Stanford: CS231n Convolutional Neural Networks for Visual Recognition

- Stanford: CS229 Problem Set Solutions

- MIT: 6.S191: Introduction to Deep Learning

- FastAI: Practical Deep Learning for Coders

- Yann leCun: Deep Learning

- Durham: Deep Learning Lectures

- Hugging Face: Deep Reinforcement Learning Class

- OpenAI: Spinning Up in Deep RL

- Amazon: Machine Learning University

- Kaggle: How Models Work

- Kaggle: Train Model with TensorFlow Cloud

- ML Basics in plain Python

- Full Stack Deep Learning

- Google: Machine Learning Crash Course with TensorFlow APIs

- Google: TensorFlow, Keras and deep learning, without a PhD

- Google: 650k+ datasets, 150+ notebooks

- In-depth introduction to machine learning in 15 hours of expert videos

- MIT: Deep Learning in Life Sciences (Spring 2021)

- Deep Learning Course Forums: Recommended Python learning resources (2019)

- KDNuggets Best Resources to Learn Natural Language Processing in 2021

- Machine Learning and Deep Learning Courses

- Wiki of courses: drizzle

ML Resources

- Keras: Code examples

- Curated list of references for MLOps

- Datasets for Machine Learning and Deep Learning

- Towards Data Science: Linear algebra cheat sheet for deep learning

- TensorFlow Quantum: library for hybrid quantum-classical machine learning

ML Research:

- Annotated Research Papers

- Papers With Code and Methods

- Computer Science Open Data (for PhD application)

- Eric Jang: How to Understand ML Papers Quickly

- John Schulman: An Opinionated Guide to ML Research

- Tom Silver: Lessons from My First Two Years of AI Research

- Chris Albon: Notes On Using Data Science & Machine Learning To Fight For Things That Matter

- Facebook AI’s full logbook for training OPT-175B

- From Statistical to Causal Learning, Schölkopf et al. 2022

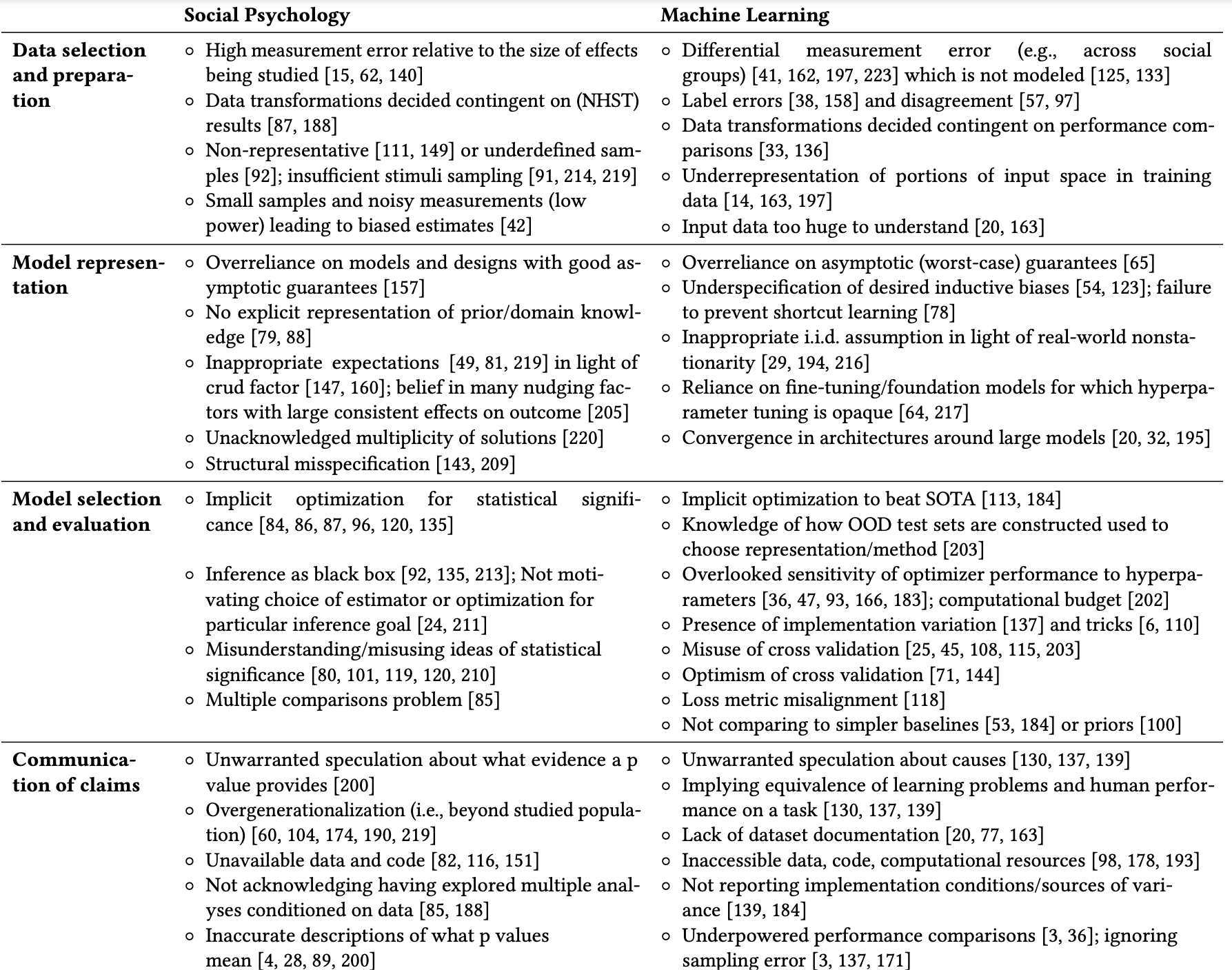

- The worst of both worlds: A comparative analysis of errors in learning from data in psychology and machine learning, Hullman et al. 2022

Replication crisis in ML research.

Transformers

- Attention Is All You Need, Vaswani et al. 2017

- Transformers for software engineers

- Jay Alammar: Visualizing A Neural Machine Translation Model, The Illustrated Transformer, and How GPT-3 Works

- One Model To Learn Them All, Kaiser et al. 2017

- Image Transformer, Parmar et al. 2018

- Language Models are Few-Shot Learners, Brown et al. 2020

- Offline Pre-trained Multi-Agent Decision Transformer: One Big Sequence Model Tackles All SMAC Tasks, Meng et al. 2021

- µTransfer: A technique for hyperparameter tuning of enormous neural networks (paper)

- FlashAttention (paper): 2-4x faster and requires 5-20x less memory than PyTorch standard attention by making attention algorithm IO-aware i.e. accounting for reads and writes between levels of GPU memory like large but (relatively) slow high-bandwidth memory (HBM) vs small but fast SRAM

- Least-to-Most Prompting Enables Complex Reasoning in Large Language Models, Zhou et al. 2022

- DeepMind’s AlphaCode (paper)

- Nvidia: Improving Diffusion Models as an Alternative To GANs and Part 2

- Google Brain’s CLIP competitor: CoCa: Contrastive Captioners are Image-Text Foundation Models, Yu et al. 2022

- Probing Vision Transformers

- Book: The Principles of Deep Learning Theory, Roberts et al. 2021

Interpretability research

- A Mathematical Framework for Transformer Circuits, Elhage et al. 2021

- In-context Learning and Induction Heads, Olsson et al. 2022

- Attention and Augmented Recurrent Neural Networks, Olah et al. 2016

- Research Debt, Olah et al. 2017

- Feature Visualization, Olah et al. 2017

- The Building Blocks of Interpretability, Olah et al. 2018

Implicit meta-learning

- One-shot Learning with Memory-Augmented Neural Networks, Santoro et al. 2016

- AI-GAs: AI-generating algorithms, an alternate paradigm for producing general artificial intelligence, Clune et al. 2020

- On Learning to Think: Algorithmic Information Theory for Novel Combinations of Reinforcement Learning Controllers and Recurrent Neural World Models, Schmidhuber 2015

- Lilian Weng on Meta-Learning: Learning to Learn Fast and Meta Reinforcement Learning

ML Scaling

- Gwern’s The Scaling Hypothesis and his up-to-date bibliography of ML scaling papers

- Understanding the generalization of ‘lottery tickets’ in neural networks, Morcos et al. 2019

- Bayesian Deep Learning and a Probabilistic Perspective of Generalization, Wilson et al. 2020

- On Linear Identifiability of Learned Representations, Roeder et al. 2020

- Logarithmic Pruning is All You Need, Orseau et al. 2020

- Direct Fit to Nature: An Evolutionary Perspective on Biological and Artificial Neural Networks, Hasson et al. 2020

- The Shape of Learning Curves: a Review, Viering et al. 2021

- Nostalgebraist: larger language models may disappoint you

Neuroscience

- The Brain as a Universal Learning Machine

- The remarkable, yet not extraordinary, human brain as a scaled-up primate brain and its associated cost, Herculano-Houzel et al. 2012

- Prefrontal cortex as a meta-reinforcement learning system, Wang et al. 2018

- Reinforcement Learning, Fast and Slow, Botvinick et al. 2019

AI Safety

- How to pursue a career in technical AI alignment

- OpenPhil: Some Background on Our Views Regarding Advanced Artificial Intelligence, Potential Risks from Advanced Artificial Intelligence: The Philanthropic Opportunity, What Do We Know about AI Timelines?, and How Much Computational Power Does It Take to Match the Human Brain?

- Future of Life Institute: AI Governance: A Research Agenda

- Machine Intelligence Research Institute: Agent Foundations for Aligning Machine Intelligence with Human Interests: A Technical Research Agenda

- DeepMind: Building safe artificial intelligence: specification, robustness, and assurance

- OpenAI: Aligning Language Models to Follow Instructions (paper) and Learning from Human Preferences

- Paul Christiano: Current work in AI alignment (video)

- Alex Flint: AI Risk for Epistemic Minimalists

- Rohin Shah: FAQ: Advice for AI alignment researchers

- Thane Ruthenis: Reshaping the AI Industry

- Victoria Krakovna: specification gaming examples in AI

- Scott Alexander: Practically-A-Book Review: Yudkowsky Contra Ngo On Agents

- Zvi: Attempted Gears Analysis of AGI Intervention Discussion With Eliezer

- Gwern: Why Tool AIs Want to Be Agent AIs and Complexity no Bar to AI

- The Ethics of Artificial Intelligence, Bostrom et al. 2011

- AGI Safety Literature Review, Everitt et al. 2018

- Unsolved Problems in ML Safety, Hendrycks et al. 2022

- An overview of 11 proposals for building safe advanced AI, Hubinger 2020

List of lists on AI safety

- Victoria Krakovna: regularly updated AI safety resource

- 80,000 Hours: AI safety syllabus

- Future of Life Institute: Benefits & Risks of Artificial Intelligence

- Lark: annual AI Alignment Literature Review and Charity Comparison

- Richard Ngo: Paul Christiano’s writings

- Steve Byrnes: AGI safety

- Rohin Shah: Alignment Newsletter

For updates and links on narrow AI, subscribe to my monthly newsletter (archive).

Endnotes

-

Markov chain & n-gram models start to fall behind; they can memorize increasingly large chunks of the training corpus, but they can’t solve increasingly critical syntactic tasks like balancing parentheses or quotes, much less start to ascend from syntax to semantics. ↩

-

As Hofstadter puts it, capabilities must disintegrate — if you successfully reduce “human reasoning”, it must be to un-reasoning atoms, not to little reasoning homunculi; or as Gwern likes to say: AI succeeds not when you anthropomorphize models, but unanthropomorphize humans. ↩

-

DALL·E 2 results have been so stunning that some mistake the gibberish to be a secret language; we’re genuinely seeing some kind of AI astrology emerge in real time. ↩

-

With 2D images solved by AI, are we following the footsteps of image/sound recording: photography -> silent movie -> movies with sound? ↩