I’ll never understand what possessed my mother to put her faith in God’s hands, rather than her local geneticist.

- Vincent Freeman

In the 1997 dystopian science fiction film Gattaca, its protagonist Vincent Freeman is labelled as an “invalid” as he was conceived outside the universal eugenics programme in which parents can choose the genetic traits inherited by their baby, and due to his genetic inferiority is relegated to the job of an office cleaner when he wishes to be an astronaut for the spaceflight conglomerate Gattaca.

The advent of new preimplantation genetic testing technologies raises the prospects of embryo selection and embryonic gene editing, which some worry will usher in an age of eugenics among a myriad of ethical concerns. Will our fate be determined by our genes? Will we create “designer babies”? Will society engage in “genetic discrimination” per Gattaca?

As usual in practical ethics, an adequate discussion of the moral issues surrounding next-generation preimplantation genetic testing requires orientation to the underlying science, which can dissolve the moral question.

- Genomics Revolution

- Polygenic Risk Scores

- Embryo Screening For Polygenic Disease Risk

- Embryo Screening For Cosmetic Traits

- Embryo Screening For Intelligence

- Gene Editing

- Applied Ethics of Positive Trait Selection

- Conclusion

Genomics Revolution

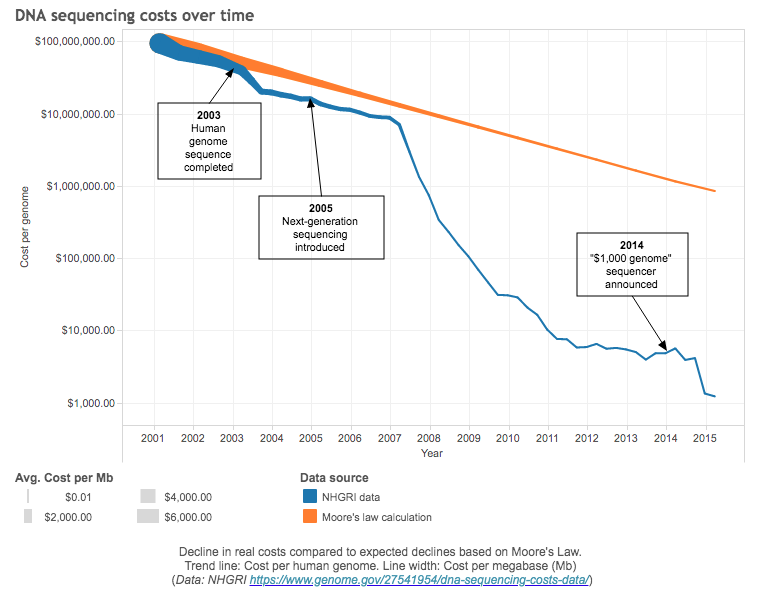

Since the release of Gattaca in 1997, the past two decades have seen a revolution in molecular genetics: the exponential reduction in cost of human whole genome sequencing (WGS) has even outpaced the Carlson curve, which predicts that the doubling of DNA sequencing technologies as measured by cost and performance would be at least as fast as Moore’s law.

Decline in real costs compared to expected declines based on Moore’s Law.

It took $5 billion (adjusted to 2020 USD) and almost 15 years for the Human Genome Project to sequence the first human genome. In 2016, Veritas Genetics began selling WGS for $999, breaking the commonly-referred commercial target of $1000. In 2020, after acquiring US’s Complete Genomics, China’s BGI claimed it could perform WGS for $100, which is the current commercial target.

This has enabled the accumulation of datasets of millions of individuals’ genomes, which enabled a myriad of genetic analysis such as genome-wide association studies (GWASs) that have identified a large number of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that are significantly associated with a wide range of complex traits (Tam et al.). However, SNPs typically have a small effect and correspond to a small fraction of truly associated genetic variants, meaning that they have limited predictive power.

Polygenic Risk Scores

One way to aggregate the effects of SNPs across the genome to estimate heritability is the polygenic risk scores (PRS) method, in which the sum of risk alleles is weighted by the risk allele effect size estimated by a GWAS on the phenotype to produce a single value estimate of genetic liability.

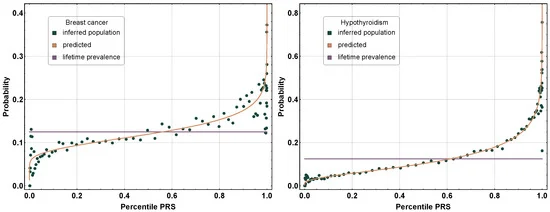

One way to characterise the predictive power of PRS is that individuals with very high PRSs will typically have an incidence rate that is many times higher than the population average. Take atrial fibrillation as an example: a 99th percentile PRS implies a ~10 fold increase in disease risk. For patients with PRS at the top percentile (e.g. obesity), the associated risk can even exceed the risk associated with well-known monogenic risk factors like BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations.

The increase in absolute risk with PRS percentile is rapid and nonlinear.

PRS is already being translated into clinical use. For example, women with BRCA1/2 mutations are routinely offered early screening, of whom only about 1 in 1000 actually result in breast or ovarian cancer. A PRS for breast cancer risk has an odds ratio per unit standard deviation of 1.47 (95% CI, 1.45 to 1.49), an order of magnitude higher than the predictive power of BRCA1/2 gene mutations. Hence, PRS can inform risk stratification to guide disease surveillance.

Embryo Screening For Polygenic Disease Risk

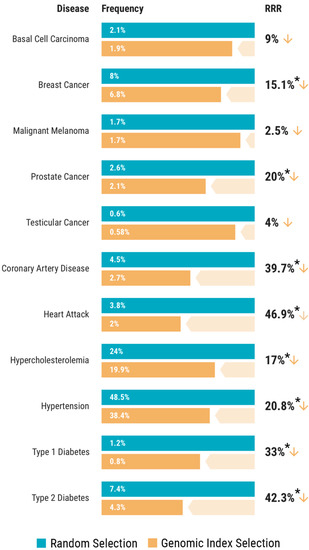

More than half a million babies are born every year via In vitro fertilisation (IVF). About 1 in 10 babies are born via IVF in Denmark. As the typical IVF cycle produces five viable embryos, the IVF parents often have to choose which specific embryo to transfer, the default method being careful microscopy-based morphology (e.g. rate of development, symmetry, general appearance) assessment. Nowadays, 40% of all IVF cycles involve preimplantation genetic testing to screen for aneuploidy (PTG-A) i.e. extra or missing chromosome (e.g. Down’s syndrome caused by trisomy 21) and chromosomal structural rearrangements (PGT-SR) i.e. translocations or inversions. Depending on familial risk factors, embryos can also be screened for monogenic disorders (PTG-M) such as Huntington’s disease or cystic fibrosis. There is even PGT for histocompatibility (HLA) for tissue donation to a sick family member. With the advent of precision embryo genotyping, preimplantation screening for polygenic disease risk (PGT-P) allows drastically more sophisticated preimplantation ranking.

The challenge in embryo genotyping is simply that embryos (typically 3-7 cells) contain very little DNA, made even more difficult due to widespread use of embryo freezing in IVF. A proprietary solution is using parental genotypes and genotypes of other embryos (siblings) to perform error correction, which can achieve genotyping accuracy of 99.6%, exceeding even that of noisier methods like clinical saliva next-generation genotyping.

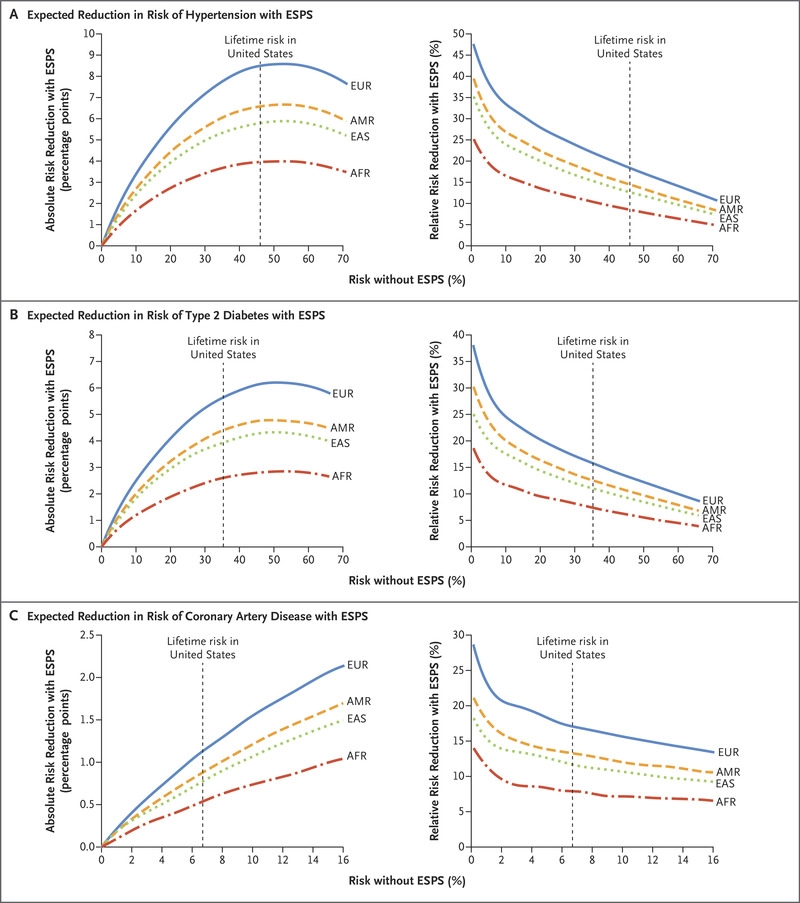

Are the levels of reductions “worth it”? Just as Vincent Freeman pondered in Gattaca, parents conceiving via IVF have to choose an embryo anyway, so instead of choosing at random, why not instead choose one in a way that halves the baby’s risk of serious diseases? In this view, embryo screening for polygenic disease risk is merely an extension of standard preimplantation genetic testing – while initially controversial, it has become merely an obscure and useful part of fertility medicine.

Embryo Screening For Cosmetic Traits

What is controversial is screening for “designer babies’’. Take skin colour for example, there is high demand for predicting it and it’s possible. The global market for skin lighteners is worth $8.6 billion, and skin whiteners account for 80% of India’s $1 billion market for moisturisers, as pale skin-tone has long been the standard of beauty in Asia. In absence of intervention from regulatory bodies, it is only a matter of time PGT-P companies start offering to test for cosmetic traits.

However, ethical controversy regarding selection for these cosmetic traits is overblown as they are often easily modified after birth, for example with hair dye or contact lenses. Also, cosmetic traits like hair colour, eye colour, and height are highly heritable. If you and your partner are both Han Chinese, the chances that your child will have blue eyes and blonde hair is negligible, so worries over selection of cosmetic traits that are not normally distributed are misled at best.

What about normally distributed non-disease traits? Take height for example: increase in height has long been linked to increased career success and life satisfaction with estimates like $800 in increased annual earnings per inch. Consider idiopathic short stature (height more than 2 standard deviations below the mean), PRS can reduce the risk of having a child with idiopathic short stature by 1.8% as compared with 10 embryos selected at random, but that only translates to an 2.5 cm increase in expected height, an outcome that is unlikely to be practically meaningful.

Fundamentally, the predictive power of polygenic scores for cometic traits is low due to their high polygenicity. Polygenic scores constructed from studies based on patients with non-European ancestry have even lower predictive power:

At the end of the day, cosmetic traits are often zero-sum, and dwarf in significance compared to personality and intelligence. Since the personality GWASes have had difficulty perhaps due to non-additivity of the relevant genes connected to predicted frequency-dependent selection, that leaves intelligence as the most significant use case for embryonic selection.

Embryo Screening For Intelligence

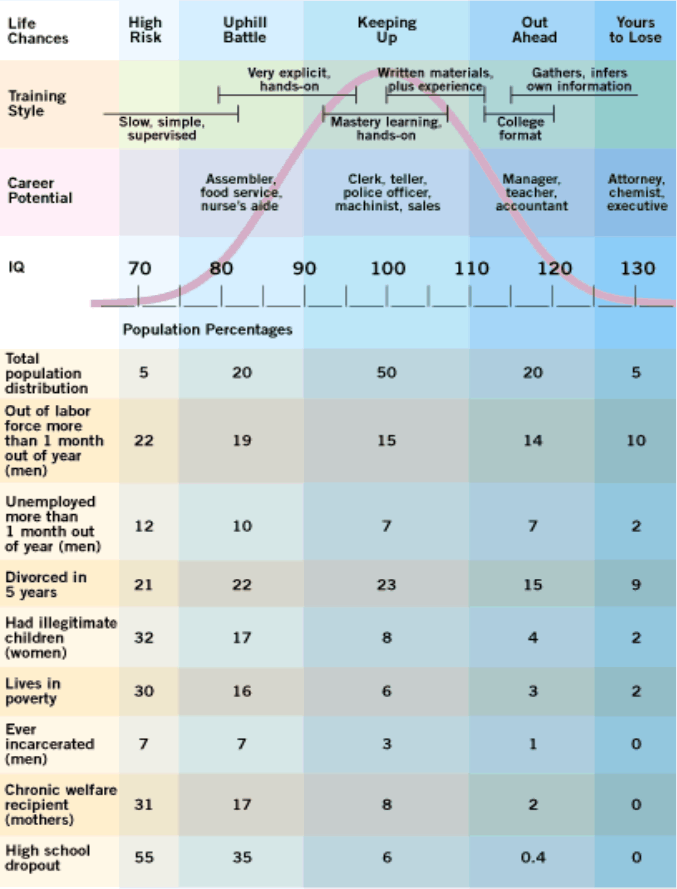

Estimating “the” value of an IQ point is difficult in its own right, but the impact of cognitive ability is undeniable. Studies in labour economics typically find that one IQ point corresponds to an increase in wages on the order of 1%. A 3 point IQ increase predicts 28% less risk of high school dropouts, 25% less risk of poverty or being jailed (men), 20% less risk of parentless children, 18% less risk of going on welfare, and 15% less risk of out-of-wedlock births:

Population distribution of IQ by intellectual capacity, common jobs, and social dysfunctionality.

The single most binding constraint on embryo selection is the number of embryos, and since sperm is effectively infinite, means the number of eggs. Unfortunately, standard IVF cycle approaches appear to have largely reached their limit, and stimulating more eggs’ release in a harvesting cycle is dangerous. The median embryo count per IVF cycle hovers around five, and there are inevitable losses in the IVF process such as when the best embryo fails to survive storage, or when the second-best fails to implant, and so on. As such, 1-in-10 embryo selection sets the upper bound of what is feasible with IVF.

The fact that traits like IQ are normally distributed also creates difficulties for selection – the further into the tail one wants to go, the larger the sample required to reach the next step. The full heritability of adult intelligence is ~0.8. Currently, polygenic scores based on the biggest GWAS yet explain 11–13% of the variance in educational attainment and 7–10% of the variance in cognitive performance. With increasing GWAS sizes, the predictive power of new polygenic scores will likely increase, but the upper limit is generally believed to be 25%. As Gwern extrapolates, that current polygenic score technology could give an average +3 IQ points (0.2 standard deviation) by implanting the highest IQ embryo; if polygenic scoring technology reached the limits of its potential (might happen within a decade or two) you could get +9 IQ points.

Hence, simple embryo selection for IQ is too limited in possible gains, requires a far too onerous process (IVF) for more than a small percentage of the population to use it, and is more or less trivial in consequences.

Gene Editing

Polygenic score technology is solving the prerequisite question of “which genes to edit”, and recent revolutions in gene editing technology like CRISPR is answering the question of “how”. CRISPR has had much more hype than embryo selection itself (the Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2020 awarded to Charpentier and Doudna) but the current family of CRISPR techniques and its alternatives can be largely dismissed due to the sheer polygenicity of the most important traits, and to a lesser extent the asymmetry of effect sizes (harmful variants are more harmful than the beneficial ones are beneficial).

The benefit of gene editing a SNP is based on the number of edits, multiplied by the SNP effect of each edit, and crucially, multiplied by the probability that the effect is causal:

- The unique edit limit safely permitted at scale is about 5.

- The SNP effect of each edit is small (e.g. 0.2 IQ points for intelligence).

- PRS do not necessarily identify the exact causal base-pair(s), sometimes just proxies for a neighbouring causal variant that happens to be usually inherited with it, as genomes are inherited in big blocks, and do not split, nor recombine at every single base-pair. If you edit a proxy, it will do nothing (or even the opposite). Attempts at “fine-mapping” GWAS to find causal SNPs estimates the causal probability to be around 10%.

This translates to a dismal 0.1 IQ point gain. Hence, CRISPR-style editing may be revolutionary in rare genetic diseases and agriculture, it will remain unimportant as far as human enhancement is concerned.

Applied Ethics of Positive Trait Selection

As the effects of gene editing and embryo selection are more or less inconsequential, ethical concerns, such as social inequality, fears of an enhancement ‘rat race’, rights and responsibilities of parents vis-à-vis their prospective offspring, and the shadow of 20th century eugenics, are all largely irrelevant in the short to medium term.

That is not to say large effects could not accumulate over multiple generations, but by then other speculative and much more radical human germline enhancement technologies such as massive multiple embryo selection, iterated embryo selection, or even genome synthesis could be mature and have magnitudes greater impact, which is outside the scope of this essay. The space of regulatory policies will be much larger: from prohibition to neutrality to strong subsidy and active promotion. Countries that prohibit them may worry about losing international competitiveness.

More abstractly, Bostrom and Ord’s Reversal Test can be used to eliminate the status quo bias in applied ethics regarding cognitive enhancement: would it be a good thing if the cognitively enhanced group instead had their cognitive capacity reduced? If we are not prepared to make the claim that the status quo would be improved if the wealthy, say, suffered slight brain damage, then the onus shifts to those who are against cognitive enhancement: they need to explain why the current cognitive ability of the potential enhancement users is at a local optimum such that both an increase and a decrease should be expected to make things worse on the whole.

The Double Reversal Test can also be applied: if a new widespread neurotoxin threatens to cause cognitive decline in potential cognitive enhancement users, would it be a net good if they could use the cognitive enhancement to stave off the impending decline? If the answer is yes, there is a strong prima facie case for thinking that it would be good overall – despite the assumed negative effect on equality – if the enhancement option is developed (Bostrom and Ord).

In Plato’s Philebus, Socrates concludes that the best life is a mixture of wisdom and pleasure. Intelligence is clearly a part of Plato’s conception of the good life:

Without the power of calculation you could not even calculate that you will get enjoyment in the future; your life would be that not of a man, but of a sea-lung or one of those marine creatures whose bodies are confined by a shell.

The principle of Procreative Beneficence states that the selection for non-disease genes which significantly impact on well-being is morally required. At this point we must move beyond the morally dubious line-drawing at the borders of “disease” and “non-disease” traits according to the disease model that most countries adopt as their regulatory frameworks. We should simply allow parents to select the children most likely to have the “best life”. If, in the end, couples wish to select a child who will have a lower chance of having the best life, they should be free to make such a choice, but that should not prevent doctors from attempting to persuade them to have the best child they can.

Conclusion

Short of radical advancement in speculative germline enhancement technologies that would require full gametogenesis control, we will not be nearly living in the world of Gattaca. Until then, state-of-the-art preimplantation genetic testing technologies can be considered as mere extensions of current screening standards. Selection for cosmetic traits and intelligence demonstrate the limitation of the disease model of regulation, but the expected gain afforded by even the upper limit of polygenic scores is severely overhyped.

Since the first IVF baby was born in 1978, many pundits proclaimed it would “forever change what it means to be human” and other similar fatuities; it did no such thing, and has since brought more than 8 million children to life, and embryo selection would probably go the same way and allow more children to have better chances to live their best lives.

The first polygenically screened baby was born in 2020 – on the 40th anniversary of the first IVF in the United States. Her name is Aurea, meaning “dawn”. Let us move on from the fear mongering of Gattaca and welcome the dawn of the new era in reproductive medicine.